- Trade, trade, glorious trade! First gameplay video of Europa Universalis IV highlights new trade system

- Europa Universalis IV Q&A, with Thomas Johansson

- The World that May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play — Part 1: Never Pick on Someone Your Own Size

- The World that May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play — Part 2: The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

- The World that May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play — Part 3: If You Can’t Beat Them…

- The World That May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play – Part 4: The Death and Rebirth of the British Empire

- The World That May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play – Part 5 (FINAL): Bend with the Wind

- Europa Universalis IV: The Verdict

- Ayutthaya Universalis: Building an Empire in Southeast Asia

- The Qing in the North: Reflections on Europa Universalis IV: Art of War

- Let’s Play EU4: Common Sense! Part 1: Welcome to Meiguo

- Let’s Play EU4: Common Sense! Pt 2: East Meets West

The World that May Have Been

Introduction

November, 1444. Under the Ming Dynasty, China is the greatest empire in the world:

Further west, the rising Ottoman Empire dominates the Middle East and is pushing into eastern Europe:

Western Europe is a chaotic patchwork of kingdoms and duchies and free cities:

The world system that existed just a century or two ago, which saw Europe and China tenuously connected by the likes of Marco Polo, has fragmented; now Europeans and Asians and Americans carry on in their separate spheres.

The world will not stay this way.

Welcome to my Let’s Play of Europa Universalis IV, a grand strategy game from Paradox Development Studio set during the early modern era of world history. I am playing as England from the earliest possible start date, 1444; I will continue until either the game ends (in the early 19th century) or I stop having fun. In that time, I’ll explore aspects of the game such as exploration, trade, diplomacy, and war. I am also playing Ironman mode, which means I have just the one save slot and can’t abuse save/reload, and I am not using any mods except for one that enlarges the font (uncomfortably small by default). Lastly, I’ll emphasise narrative rather than gameplay, and if I do interject with an “out of universe” comment, I’ll mark it clearly, (like so). Onward to the game!

Part 1: Never Pick on Someone Your Own Size

1444 to 1469

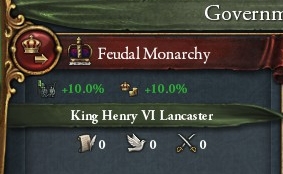

King Henry VI, Queen Anne I

War has many faces, yet one face everywhere: anguish for the victims in the middle of it. – Lauro Martines, Furies: War in Europe 1450-1700

The winter of 1444 saw the Hundred Years’ War between England and France enter its twilight. 17,000 English soldiers huddled in continental garrisons, split between northern and western France; confronting them were over 40,000 French soldiers on the northern front alone. Henry V of England had beaten those odds a generation earlier – but his son, the reigning king in 1444, was no Henry V.

(In-game, monarchs are rated along three axes: administrative, diplomatic, and military skill. England’s starting king, Henry VI, has a zero in all three.)

We know much about English policy in this period from the writings of Christoffel van Renesse, a man from Calais who became treasurer to Henry VI in his late twenties. Van Renesse stayed in that post as other advisors came and went, and though lacking in radical ideas, he kept England’s finances on a stable footing over the decades to come.

(Van Renesse was a randomly generated in-game character, not a historical person; the above screenshot shows him a couple of decades on. “Monarch points”, a vital in-game currency used for everything from peace offers to technology research, are determined by monarch skill plus advisor skill plus a flat base amount, and better advisors are extremely expensive. In the above picture, van Renesse only contributed a single administrative point per month vs Glynn Powell’s two diplomatic points, but Powell cost more than four times the upkeep – money I eventually couldn’t afford.)

As England’s mightiest men conferred, van Renesse proposed a bold plan. The playwright Wilbur Shakesheff put the following words in his mouth:

VAN RENESSE: My lords, the French rose is sweet – but its thorns are 40,000 strong. Why not look elsewhere? The fruits of the north, I hear, are as sweet, and ripe, and unguarded, too.

(Missions are optional short-term objectives that are randomly generated three at a time. Getting the mission to vassalise Scotland was a big stroke of luck: at the start of the game Scotland has no allies and a much smaller army than England, and that mission gave me a casus belli to hit Scotland while the opportunity was there.)

Over the next few weeks, English ships began ferrying the troops back from French soil, all but a token rearguard; and not a moment too soon. Even as the French marched in to lay siege to the English castles in Normandy and Guyenne, the people of Scotland woke up to find English soldiers trampling their fields, led by the flower of the English nobility and Henry VI himself. For all his failings as a monarch, Henry VI could still inspire the troops, and soon the small Scottish army was swept aside:

(In one of those funny rolls of the dice, despite Henry VI’s terrible stats as a monarch, he actually turned into a pretty decent general. The sacrificial rearguard in France was the result of a dumb mistake – I didn’t have enough ships to load all my soldiers, so the game filled the ships up to capacity and left the surplus troops stranded on the beach. Previous games would have flat-out refused to let me load anyone, so I never realised my mistake until it was too late.)

After the destruction of the Scottish army, and with English troops occupying ever more of the country, it was only a matter of time until the Scottish King James was forced to proclaim himself vassal to the king of England. Later historians, who did not see the blood or smell the death, called it a splendid little war.

The price paid was the abandonment of England’s continental territories to France, all but the toehold of Calais. Still, many English lords remained optimistic they could recover the lost land. England retained claims on those territories, and English diplomacy was bearing fruit; in the coming years, England allied with Denmark and Austria, and cemented its friendship with traditional ally Portugal. When the duchy of Burgundy disintegrated, its lands fell into the hands of the French and Austrians, who now shared a border. The Anglo-Austrian alliance seemed prescient. Surely England and Austria, together, would form a strong counterweight to France.

It would be some time before that alliance was tested. Personal tragedy for Henry VI, when his son Thomas died, was followed soon afterwards by the birth of a daughter, Anne. Concerns about the succession figure prominently in van Renesse’s documents from this time, but the intervening years were peaceful, save for a brief English expedition to punish – and force into vassalage – the minor Irish kingdom of Tyrone. Finally, in 1458, the king of France launched a campaign against Brittany — and Henry VI and his advisors saw their opportunity. With her allies in tow, England declared war on France:

Unfortunately, things did not go according to plan:

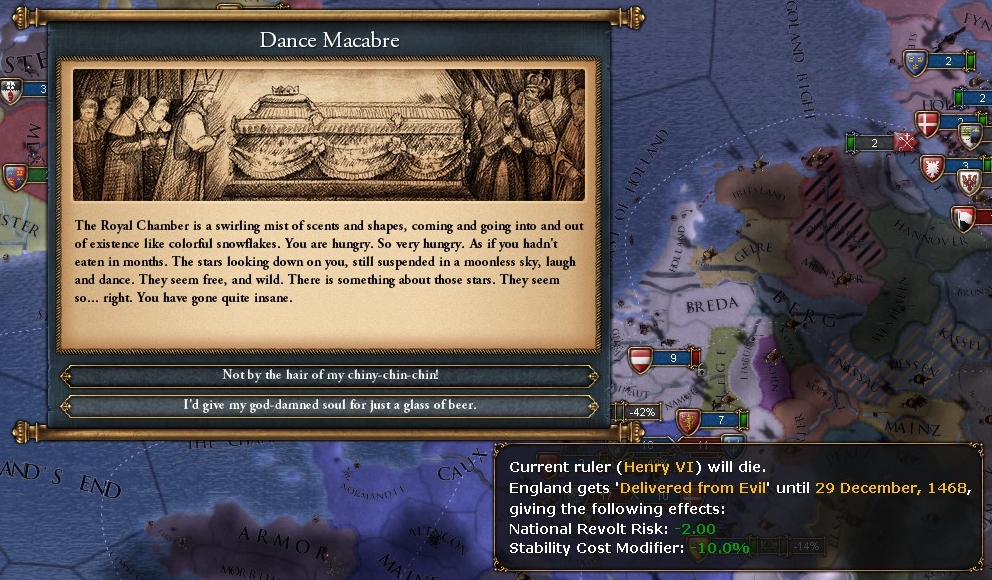

The French won battle after battle, and meanwhile, England’s ally Austria was increasingly distracted by rivals closer to home in Germany. In the middle of the war, Henry VI abruptly died – according to some accounts, he dropped dead after hearing of the latest English defeat:

The plodding, ineffectual regency council that replaced him was little better. And when a pretender rose against Henry’s infant daughter Anne, in one of the ironies of history, the remnants of the English army needed the help of loyal Scottish soldiers to put down the revolt.

(The regency council also had stats of 0/0/0, the same as Henry VI. Ouch.)

In the end, England – out of cash, out of manpower – came grovelling for peace in 1464. Under the resulting treaty, England handed over Calais to France; renounced all claims on continental territory; and most humiliatingly of all, granted independence to Wales and Cornwall. The Hundred Years’ War was over.

Christoffel van Renesse died five years after the end of the war, in 1469. Many blamed him for the original “Scotland first” policy that had seen England neglect the continent, and he himself lost his estates around Calais to the advancing French army. Yet he retained his post as treasurer to young Queen Anne, who trusted him like a father. During the disastrous war, he had cheered Anne up by encouraging her fascination with explorers, and navigators, and distant China; and while little came of this at first, the seed of curiosity he planted in Anne’s mind would be his most lasting legacy in the decades to come.

The comments above are based on a review copy supplied by publisher Paradox Interactive.

Discover more from Matchsticks for my Eyes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I like where this is headed!

Nice one!

Thanks, I’m glad you liked it!