- Trade, trade, glorious trade! First gameplay video of Europa Universalis IV highlights new trade system

- Europa Universalis IV Q&A, with Thomas Johansson

- The World that May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play — Part 1: Never Pick on Someone Your Own Size

- The World that May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play — Part 2: The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

- The World that May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play — Part 3: If You Can’t Beat Them…

- The World That May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play – Part 4: The Death and Rebirth of the British Empire

- The World That May Have Been, a Europa Universalis IV Let’s Play – Part 5 (FINAL): Bend with the Wind

- Europa Universalis IV: The Verdict

- Ayutthaya Universalis: Building an Empire in Southeast Asia

- The Qing in the North: Reflections on Europa Universalis IV: Art of War

- Let’s Play EU4: Common Sense! Part 1: Welcome to Meiguo

- Let’s Play EU4: Common Sense! Pt 2: East Meets West

In 1665, Great Britain lay in ruins, her navy and trade fleets sunk, her cities occupied by French soldiers. It was the culmination of a series of unsuccessful wars waged throughout the 17th century, and as His Britannic Majesty’s hangdog envoys filed into the negotiating room, it was in doubt whether Britain would even survive. Previous wars had seen Wales, Cornwall, Northumberland lost, albeit temporarily. Could her victorious enemies even force her to give up Scotland?

The troubles had begun in the year 1600, when Great Britain had barely found its feet after the last century’s Wars of Religion. Decades earlier, Catholic rebels had not just wrested Ireland from the British crown; they had pledged their fealty to France. For Britain’s king, Octavius I, this was intolerable. His plan seemed foolproof: the British fleet would keep the French bottled up in harbour, Britain’s Austrian and Spanish allies would keep the French army busy on the European mainland, and Britain’s own modest army could seize an undefended Ireland. What could go wrong?

As it turned out, plenty. Distracted by rivals closer to home, the Austrians soon signed peace with France. The French demolished the Spanish army, and occupied Spain. Britain in turn occupied Ireland, but compared to the victories the French had racked up on the continent, that mattered little. The war settled into stalemate – the French fleet unable to match the British, the British army unable to match the French – and it could have dragged on forever.

(If this were a normal war Spain would have separately capitulated, but Spain and I were in a coalition war, in which individual coalition members can’t sign separate peace treaties. This rule seems a little odd – after all, if Napoleon could pick off coalition members, why can’t we?)

But then, in the late 1620s, Austria petitioned Britain for help against the Dutch. London accepted. It was a catastrophic mistake. Scattered across the French coast, Britain’s blockading squadrons were easy prey for the combined Franco-Dutch battle fleet, and after that, the war was a foregone conclusion. A navy-less Britain renounced her claims upon Ireland, and granted independence to Wales (for the second time in two centuries) and Northumberland.

The embittered King Octavius, and his successors, drew a lesson from this: “steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world”. Unfortunately, it was the wrong lesson. In the years following the war, Britain’s relationships with Austria and Spain withered on the vine; and the country turned her back on European politics to pursue a maritime empire in Asia. At first, this seemed successful, as British colonies sprang up as far afield as western Java, and as British merchants began flooding into Asian ports. Quick, easy military campaigns brought Wales and Northumberland back into the fold. There was even a small victory against France, when a renewed Franco-Spanish/Portuguese war allowed Britain to reclaim the northern tip of Ireland and carve two independent kingdoms, Normandy and a reborn Burgundy, out of the French coastline.

But new territories meant new enemies. In the Middle East, the powerful sultanate of Oman declared a holy war against Britain (cynics reckoned the sultan of Oman had a rather more practical motive, namely chasing out the British traders who had flocked to the region.) In West Africa, an over-eager British colonial governor fabricated claims on nearby lands held by the Mali Empire, but his invasion backfired disastrously when Mali’s large, relatively modern armies brushed aside the small British garrison and seized the British colony itself.

(The Malian fiasco was the result of me making the most elementary mistake in the book – not checking the capability of the Malian army BEFORE I went to war. Oops.)

With half the Royal Navy fighting Oman on the far side of the world, the leaders of the Netherlands saw their opportunity. In January 1660, the Netherlands declared war on Great Britain, and they brought Portugal and France along with them. Their combined forces destroyed first the British fleet in home waters, then the fleet returning from Oman. The French army annihilated its British counterpart outside the walls of London. It seemed over for the British Empire.

Except it wasn’t.

At the peace conference, the allies did not press their advantage: their demands boiled down to a handful of distant colonies. The war had cost British (and allied) households dearly in blood: by its end, there was not a single British warship left afloat. It had cost British monarchs treasure and prestige. But the territory of Great Britain and almost all her overseas empire remained intact.

Upon this foundation, it was left to another British king named Octavius to rebuild British power. Octavius II shared a goal with his great-grandfather: turning Britain into the world’s greatest commercial nation. But they could not have gone about it more differently. Octavius I had confronted other European rivals; Octavius II did not. Octavius I had eschewed alliances; Octavius II allied with the Protestant naval power of Denmark, providing a shield while Britain slowly recovered.

(At this point I belatedly realised that if I had strong allies, computer players would be less likely to pick fights with me!)

Just as importantly, when the rebuilt British trade fleets returned to America and Africa and Asia, Octavius II made it clear they were just that – trade fleets. The Malian colony had originally been established to provide a base for British trade ships, and in the first half of the seventeenth century, British hotheads dreamed of conquering ports in India for the same purpose. Under Octavius II, such talk died away. The king pointed out, quite reasonably, that if all Britain wanted was ports for the Royal Navy and the trade fleets, why not simply ask?

The results were spectacular. For hundreds of years, since the Navigator Queen, Britons had dreamed of trade with China; one early North American explorer had even brought along a fine Chinese robe, in case he should find a way west to the Ming court. During the reign of Octavius II, the dream became reality. By the 1680s, Britain’s merchants roamed as far afield as the Yangtze Delta, buying porcelain far superior to anything Europeans could produce. The local kingdoms, successors to the vanished Ming dynasty, were all too glad to allow access to their ports.

(There really was a North American explorer who wore a Chinese robe, although in our history it was a Frenchman, Jean Nicolet.)

After leaving China, the trade flowed through the Straits of Malacca, the ancient gateway between the Indian and Pacific oceans. British trade fleets carried it west, stopping at Indian ports controlled by the mighty empire of Vijayanagar, and south through the Red Sea, where Oman had abandoned its attempt to drive the British out with force. After rounding the Cape of Good Hope, mostly in Portuguese and other European ships, the trade reached West Africa, where British trade fleets (now based at Malian ports, following Octavius II’s policy of detente) entered the equation again. Eventually, the British ships would sail into London; their porcelain and spices and textiles would finish in houses around the land; and some of the revenues would flow into royal coffers. How much? Enough to make the British crown the wealthiest in the world.

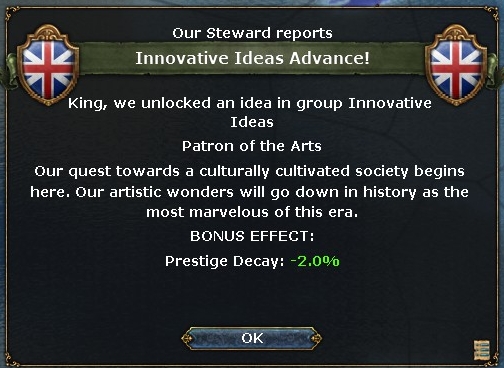

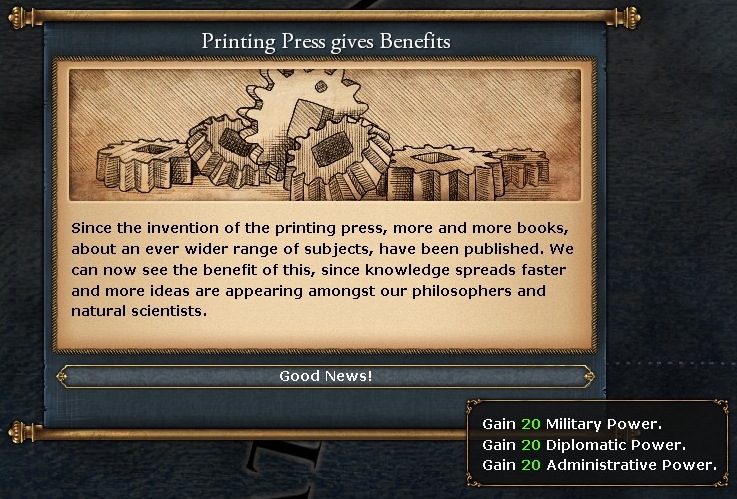

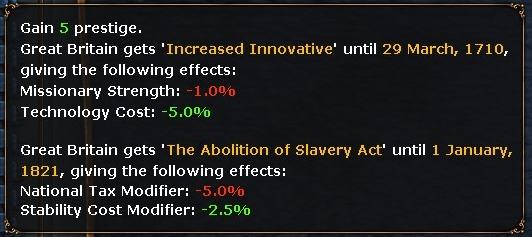

That money repaid the debts of the British crown. That money contributed to the intellectual and cultural ferment that swept Britain in the 1690s, and perhaps even to London’s decision to abolish slavery around this time:

(I’m not sure whether the “Innovative” national ideas, which confer a host of nice-but-modest bonuses, were the optimal choice. But for roleplay reasons, this was essential – we know what the fruits of scientific innovation were in real life! For similar reasons, abolishing slavery, a choice that becomes available starting in 1700, was a no-brainer.)

And most of all, that money allowed Octavius II to reveal his true colours. In 1694, the conciliatory foreign policy he had pursued for decades came to an abrupt end. Britain declared war on the Netherlands to reclaim the two provinces she had lost in the Americas, a generation earlier. Now it was the British battle fleet’s turn to destroy its Dutch counterpart:

British soldiers set about subjugating the Dutch colonies in North America, and for the first time in hundreds of years, London resolved on a land campaign on the European continent. Thousands of mercenaries flocked to the British banner, recruiting sergeants fanned out across the British Isles, and in the year 1700, the mustered British army landed in the friendly kingdom of Burgundy, just across the border from the Netherlands. When the British crossed the border, the Dutch army marched to confront them. The British soldiers, drilled and disciplined, were not the rabble the French had driven off the continent 250 years earlier; but still it seemed superior Dutch generalship would prevail. Then a second British army arrived on the Dutch flank.

It was the first great triumph of an army from the British Isles against another European foe since Agincourt, and what a triumph it was. That day the British won the war, although they took years more to mop up the fortresses dotting the Dutch countryside. And when it came time to settle a peace, Britain would not make the same mistake that her victorious enemies had made decades earlier: her negotiators set out to ensure the Dutch would never be a threat again. The Dutch handed over most of the North American seaboard to Britain, but the real thrust of the treaty was the dismemberment of the Netherlands itself. The Dutch heartland, Holland and Flanders, would henceforth become sovereign – and pro-British – states, while swathes of remaining Dutch territory would be given to neutral Austria. Left with a bare handful of coastline, the Netherlands was destroyed as a naval power.

In the end, Octavius II did not live to see his triumph: it was his son King Alfred who dictated terms to the Dutch. In the coming decades, Alfred would fight – and win – his own wars, against France or the rump Netherlands or both at the same time. But just as the fall of the Netherlands in 1702 was the springboard for Britain’s return to continental Europe, it was Octavius’ policies over the 1670s and 1680s that provided the bedrock for Alfred’s victories. Patient, clever, and ultimately ruthless, Octavius II must rank as one of Britain’s most capable monarchs of the period. His ancient namesake would have been proud.

This Let’s Play is based on a copy supplied by publisher Paradox Interactive.

Discover more from Matchsticks for my Eyes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

NICE!

Thanks, exactly how I felt!

Wow! Man this is a really good read! Im liking the whole thing so far, good job :D