I’ve finished two games of Humankind, the new historical 4X strategy game from Amplitude. It’s really good — better than I had expected. It’s also a lot more challenging, and I think that’s why I’m enjoying it.

Comparisons to Civilization will be inevitable — I’ll go out on a limb and say that at a design level, I think Humankind does Civ better than the most recent Civ games. While I play and enjoy Civilization VI as a “numbers go up” game where the fun is in designing and building powerhouse cities, that game’s AI is simply not aggressive or tactically competent enough to feel like a true rival. If I do lose a game of Civ VI, it’s because I did a poor job of making the numbers go up, hence allowing the computer to reach the victory conditions first.

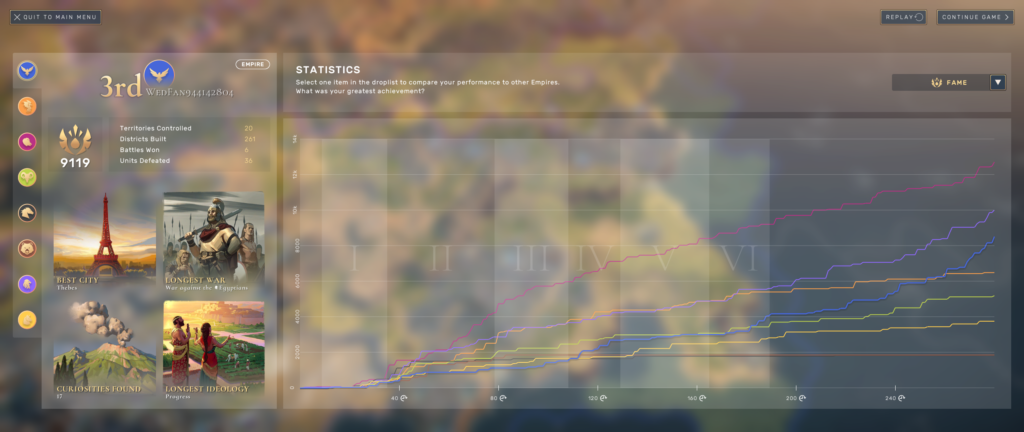

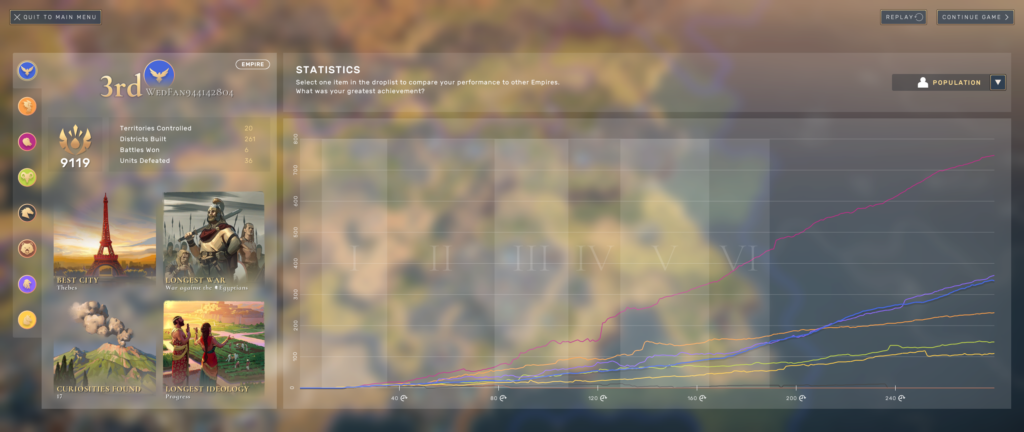

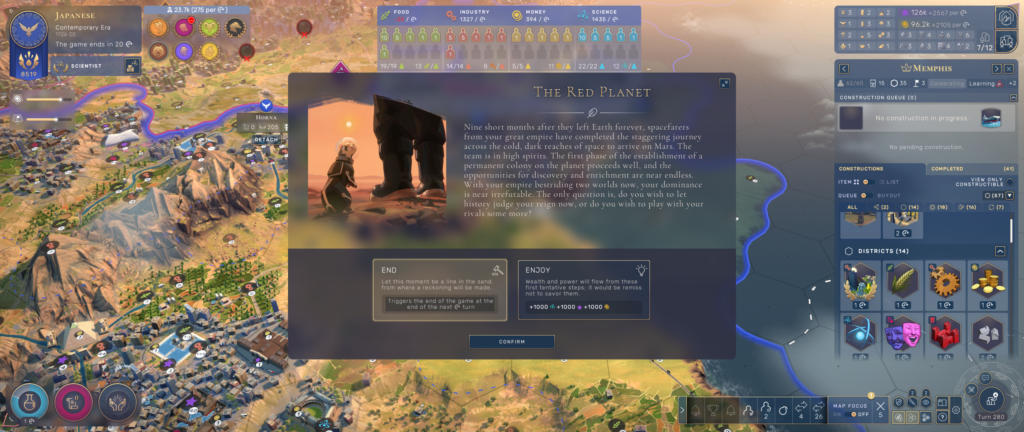

By contrast, playing on Empire difficulty (5 out of 7 — I agree with the consensus that experienced 4X / strategy gamers should crank the difficulty up), Humankind consistently puts me under pressure — I have yet to win a single game. In my first game, I barely scraped into #2 place on the final turn. In my second game, I came a more distant #3 — and I consider that an accomplishment, given that at one point, I was dead last! This kind of game is all about snowballing — setting up a virtuous cycle of more food, production, and science, which allows more upgrades, which allow more food, production, and science — and it’s notable that the computer knows how to do that. In my second game, one AI player built a gigantic lead by playing as a series of agrarian cultures, amassing a huge population (at one point its cities were size 40+ at a time when mine were in the 20s), and conquering a neighbour early on. It hit the final era well before me, and won by a commanding margin.

Not only is the computer capable of building strong empires, it’s perfectly willing to muster its armies and batter down my gates, just as Civ IV‘s AI did back in the day. My first game was very military-focused — the computer was much more bellicose than I expected, and from the ancient through to the early modern eras, I was almost constantly at war. An early-game rush from the neighbouring player made me fight for my life — the computer cleverly took advantage of my neglecting the military. Subsequently my neighbours hated me for most of the game, until something changed and most of them suddenly wanted to be my friend — my best guess is that when I converted to the dominant religion on the continent, that removed the main source of friction.

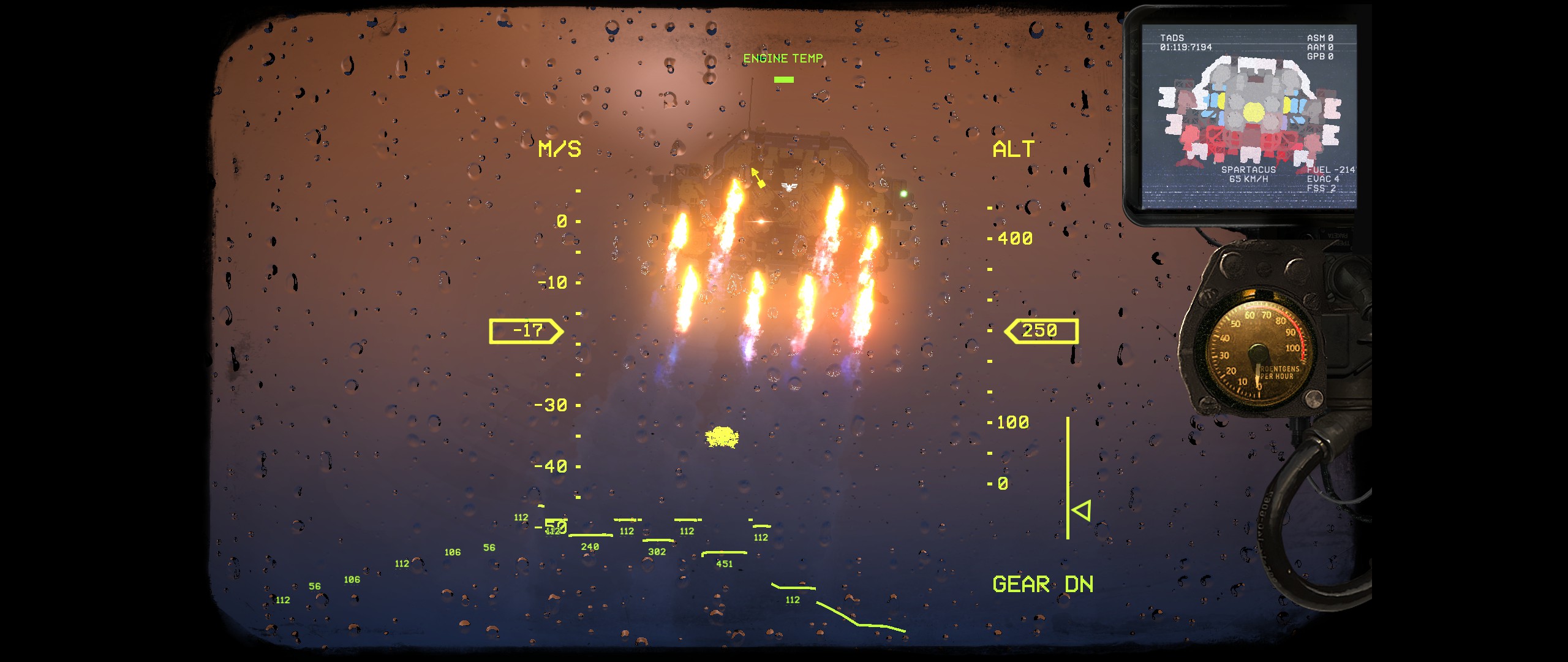

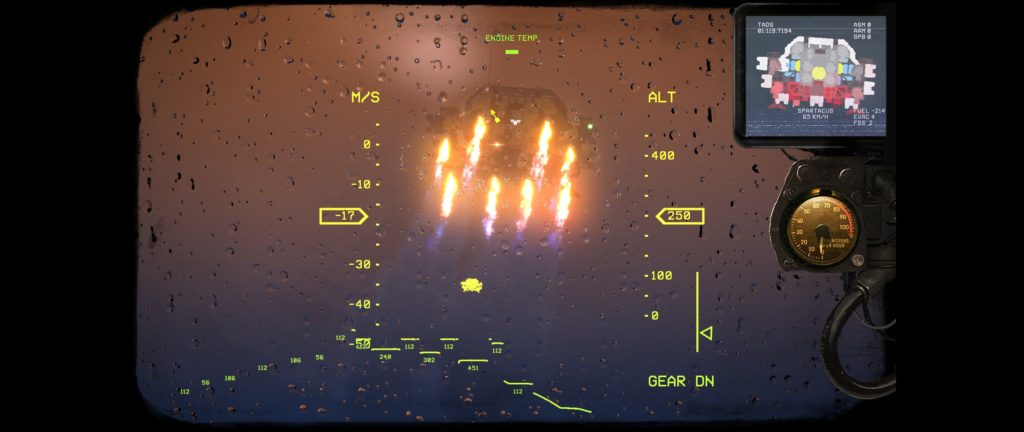

Combat itself is solid and the individual battles are generally interesting to play out. Early on, the rule is “strong melee units in front, archers behind”. New eras introduce new wrinkles — for instance, early gunpowder units can’t move and attack in the same turn, so my Medieval-era Varangians were still extremely useful for flanking and charging enemies even once I started fielding arquebusiers. By the modern era, battleships and bombers can deliver devastating bombardments to support land battles. I really like that cities generate freespawn militia (this is what saved me from that first rush!), and the clever way in which sieges gradually shift the advantage from the defender to the attacker over time, as powerful siege engines go up. Choke points are important, and help a defender against a numerically superior attacker. I do find it unintuitive to read the terrain — it’s often unclear to me which differences in elevation can be traversed by units.

So far I have a pretty good grasp on the military aspects of Humankind, to the point where I can consistently beat the computer on the battlefield. In contrast, I’m still learning how Humankind’s economic “engine” works — the key seems to be a combination of territorial expansion; placing districts to take advantage of adjacency bonuses; and savvy use of each culture’s powerful unique buildings. It seems easier to amass science than the other resources — is that actually the case, or is that simply because my playstyle focuses on science? There are other systems I have yet to engage with, such as religion and cultural influence — I don’t know how important or deep they are.

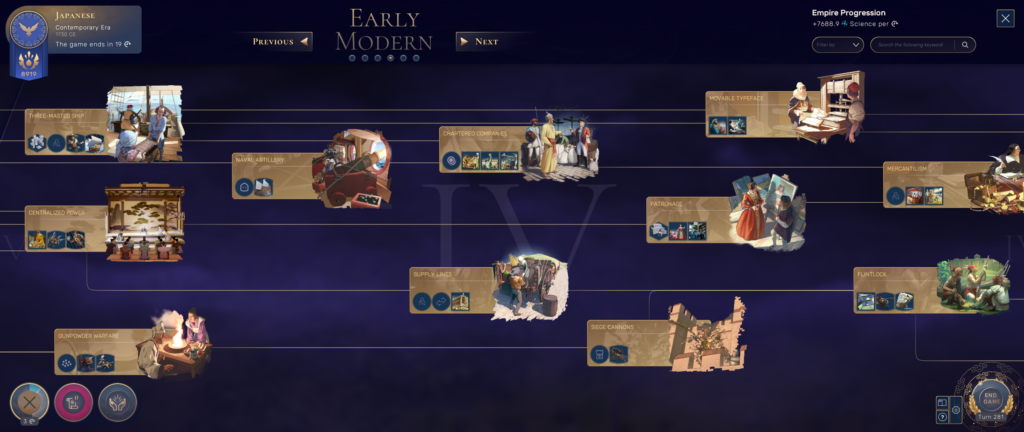

One area that could do with fine-tuning is the final, modern era. The foundations are there and the ideas are interesting – for instance, when pollution caused a penalty to food production on each tile of a large city, I sat up and took notice. When it comes to implementation, the numbers feel as though they still need tweaks: science costs in the final era seem a little low, production costs seem a little (or more than a little) high, and the pace feels a little too brisk, as if the developers overcompensated in a bid to avoid Civilization’s sluggish late game.

One thing I do like is the game’s signature mechanic: the player chooses a new culture for each era, instead of being locked into one for the entire game. The decision to change culture plays into what is required at any given moment. In my first game, I started as the Zhou in the ancient era to take advantage of their science bonus. When it became clear that I’d be locked into brutal wars, I needed the toughest fighters I could find — I chose the Romans, and steamrolled my foes with Rome’s unique units. After that I continued as the Byzantines — with their equally impressive Varangians — in the medieval era, then finished with a string of science cultures: Joseon, industrial-age France, and modern Japan. I love that these options all feel cool and powerful — this is the right way to implement a philosophy of “interesting decisions”.

Edit: I haven’t found bugs to be too bad. So far I’ve encountered 2 crashes (not a big deal, as the game auto-saves each turn) and a couple of cosmetic glitches. The most concerning is that the computer player in a particular slot (purple) reportedly receives automatic influence upon independent minor factions — hopefully Amplitude will address this soon.

A final point is that the art lives up to Amplitude’s typical high standard. Special mention for the art that illustrates each technology in the game — with a quick scroll left and right along the tech tree, I can see Humankind’s (and humankind’s) progress from the pyramids to the space age.

Overall, I’m very positive so far. Humankind already has the “just one more turn” magic backed by solid strategic gameplay, and I expect it will have room to grow via DLC and patches. I look forward to my next game!