We’re back with a lovely, gentle, relaxing piece that plays on the strategic map of Total War: Three Kingdoms. While I’ve tended to feature Total War music from Jeff Van Dyck’s era (up to Shogun 2), this is a gem from the more recent games. I think it’s great ambient music, whether choosing the next move in-game or focusing on a project in real life. Enjoy!

Month: July 2024

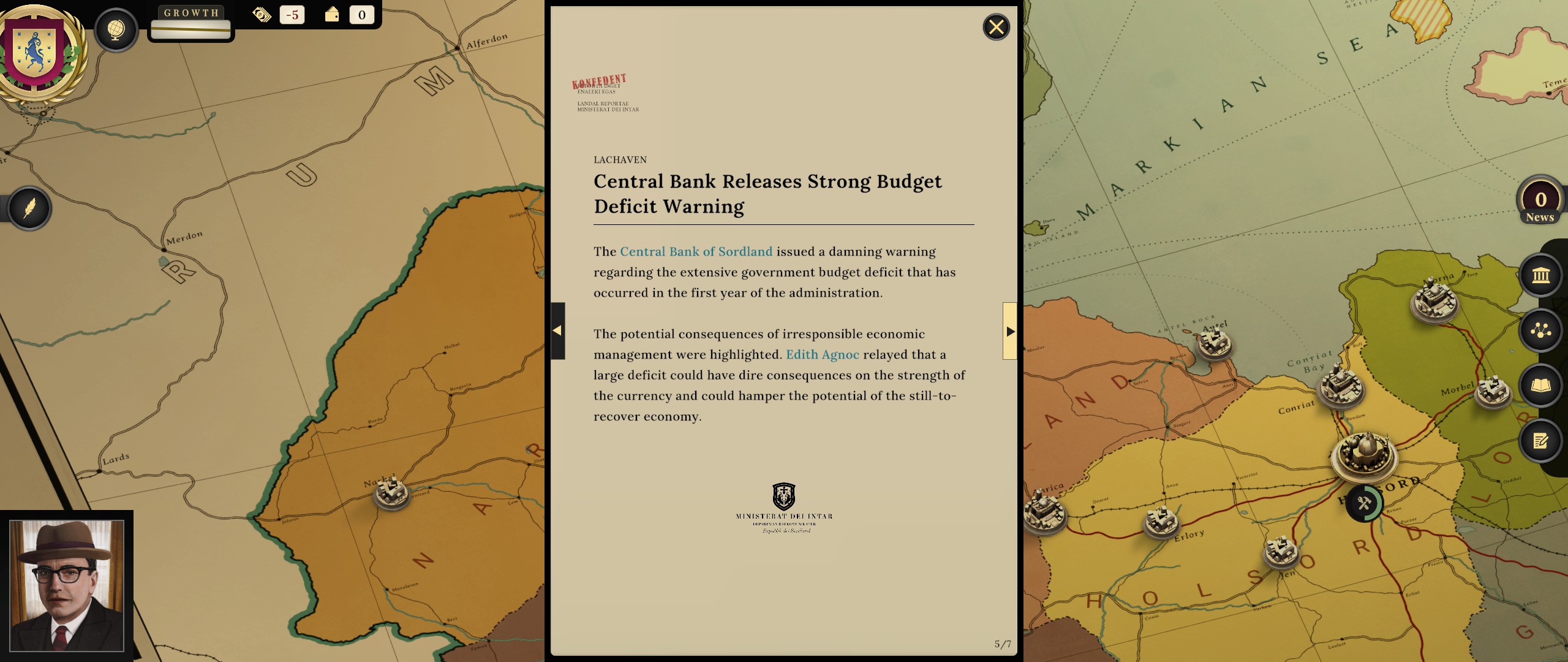

Suzerain: a narrative game that brings policy & politics to life

Suzerain is a work of interactive fiction about leading a country, set in an imaginary world reminiscent of the early Cold War. Since its launch several years ago on Steam, it has become a cult classic, and both the base game and DLC impressed me when I played them earlier this year. They tell engaging stories that feel true to their subject, making them well worth a look for news and politics junkies.

Enjoying this site? Subscribe to updates here:

Text-heavy interactive fiction

So far, there are two stories available:

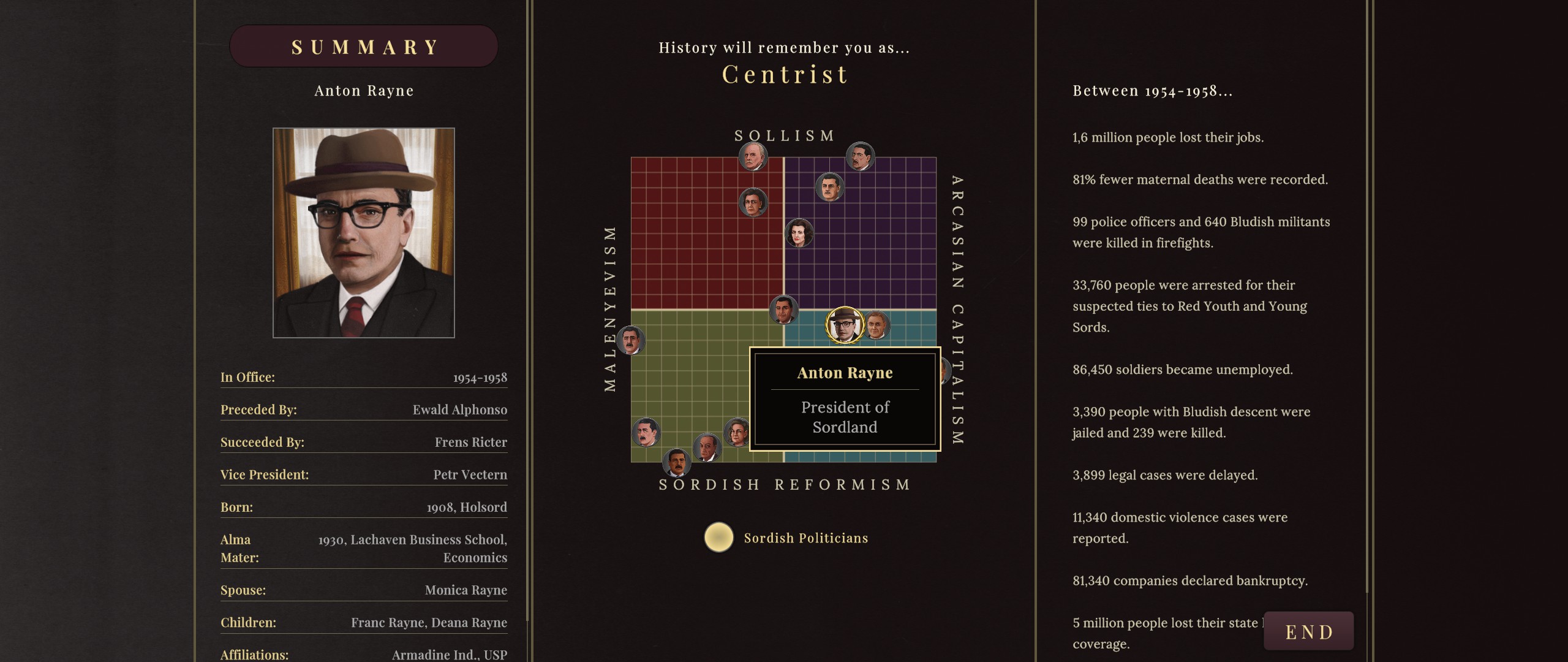

- The base game casts the player as Anton Rayne, the newly elected president of Sordland, as the country emerges from 20 years of one-man rule.

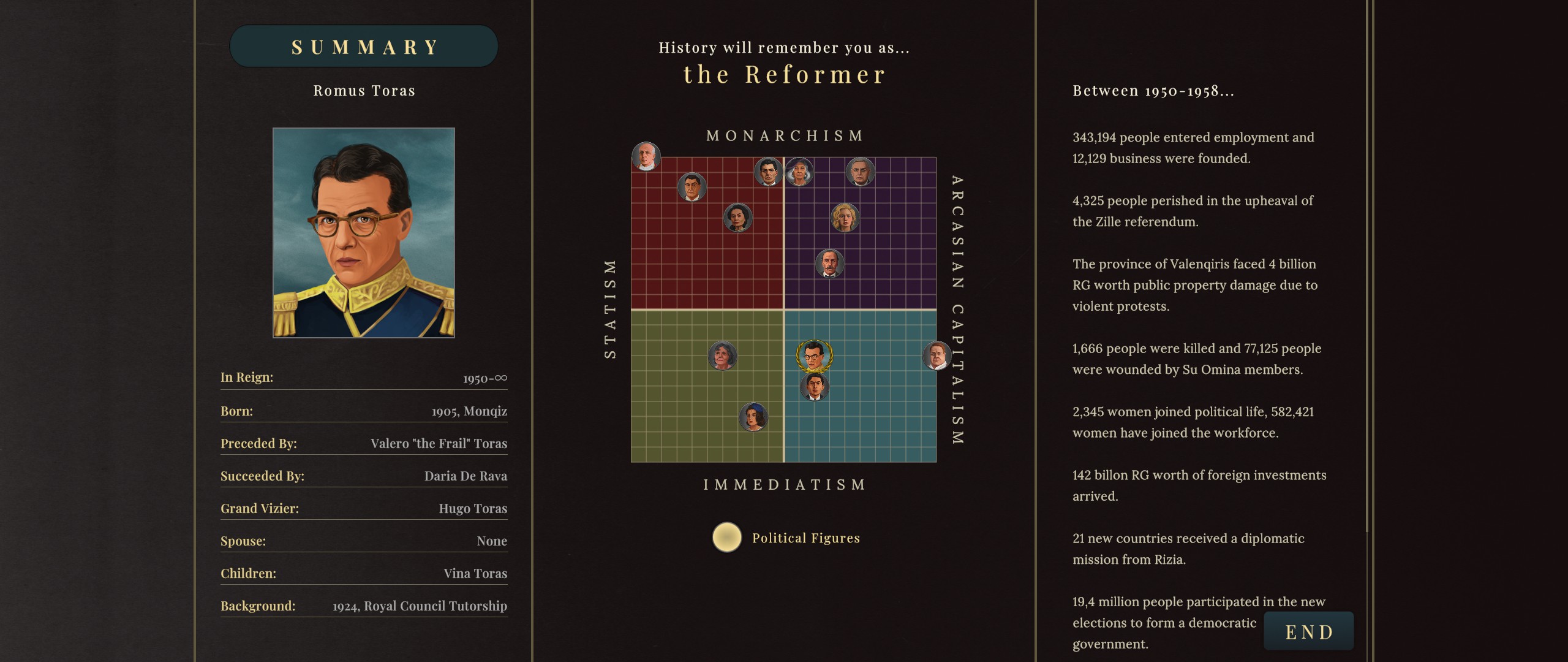

- The “Kingdom of Rizia” DLC shifts the focus to a new country and a new character, King Romus Toras.

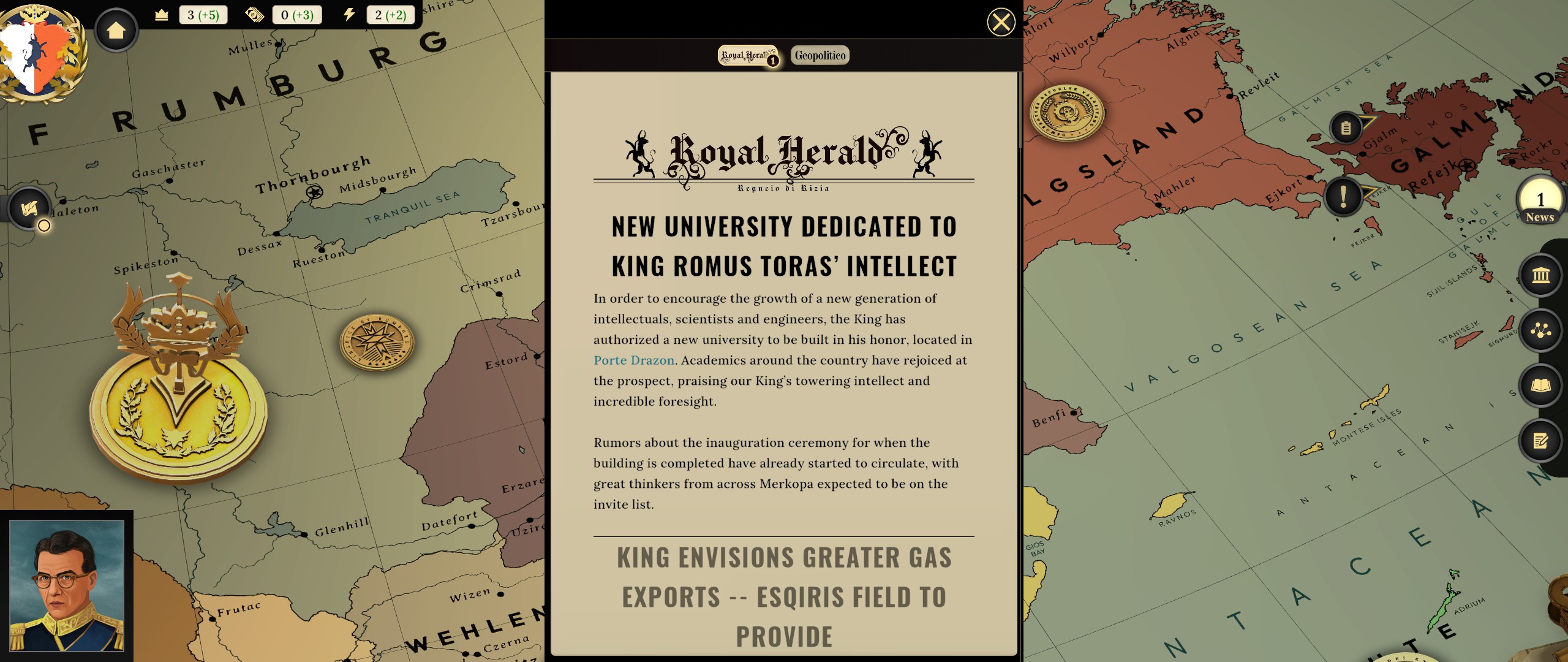

In either case, playing Suzerain involves a lot of reading. Players read story events as they unfold, proceed through dialogue, and choose conversation responses to progress the story. Occasionally there is legislation to approve or veto. “Rizia” allows the player to be more proactive, as King Romus can issue royal decrees that might include starting work on a new dam, exploring for resources, consolidating provincial militias, or funding a new university.

Instead of the numerical resources and stats of a strategy game, Suzerain presents information in a qualitative way. Characters may warn in dialogue that a problem is brewing. Clicking on cities will show modifiers that currently apply to their regions. A sidebar menu keeps track of various indicators, ranging from school quality to the strength of the air force. Finally, the many newspapers of Suzerain’s world will comment on current events from their different perspectives — some more neutral than others.

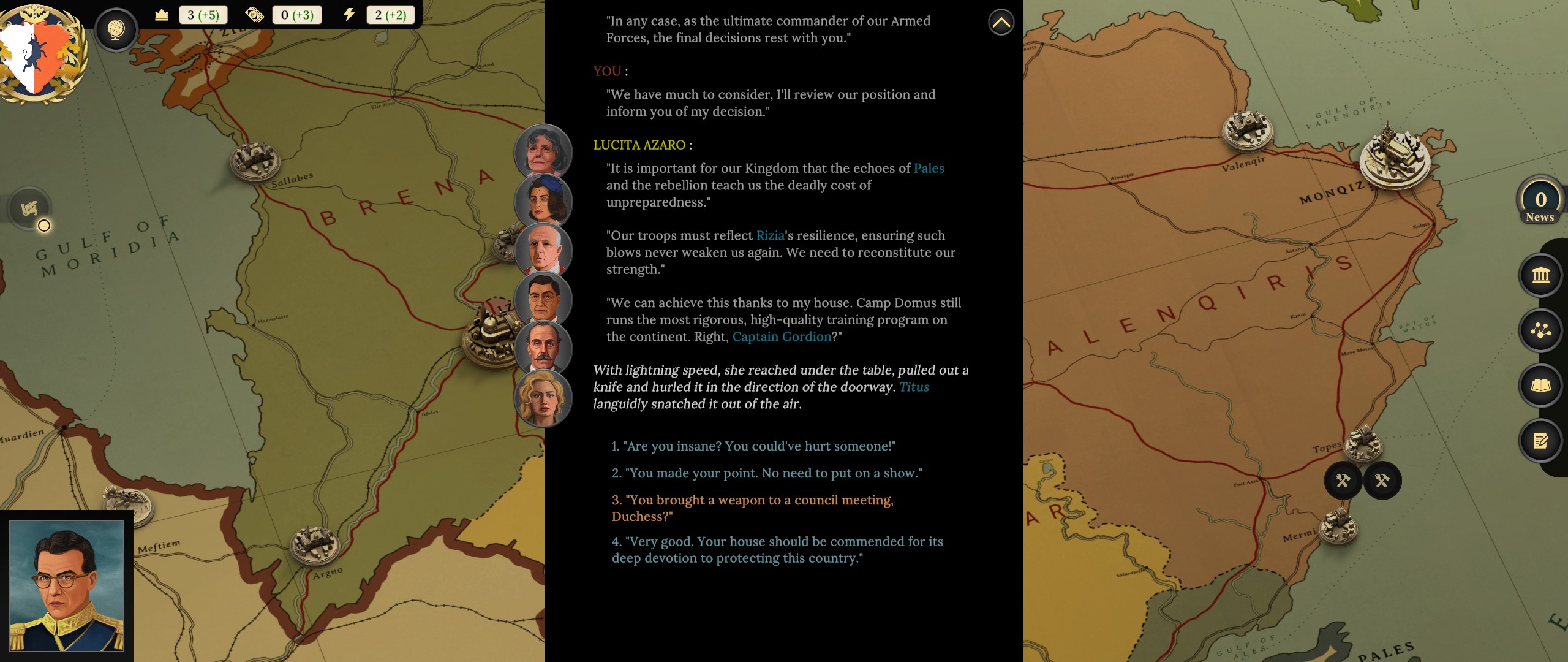

Throughout, the writing is effective. The characters feel like people rather than strawmen, and events can be gripping — or downright stressful. The prose can be slightly formal, wordy, or stilted, although I can forgive it in the case of dialogue explaining policy options — that can be justified by the game’s need to explain information.

Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown

Whether in Sordland or in Rizia, the player’s nemesis is “events, dear boy, events”. Plot twists come thick and fast, presenting a constant stream of crises. And on a first game, it’s necessary to work out characters’ loyalties on the fly. Who supports which cause, who can be a useful ally, who is out for themselves, and who are the idealists and the patriots?

Compounding this is the messy situation in which both countries begin the game:

- Sordland, in particular, rests on a knife’s edge: the economy is both statist and riddled with cronyism, the recently retired strongman still commands an influential “old guard” of loyalists, there is significant tension between the majority Sords and the minority Bluds, and an expansionist neighbour is watching with hungry eyes.

- Rizia is better placed, but faces its own challenges. While the Rizians may dream of regaining lost lands, the current rulers of those lands have ideas — and allies — of their own. Domestically, while King Romus is an absolute monarch in theory, in practice his power is checked by the aristocratic families who rule Rizia’s component duchies.

My base game run was a disaster. I set out to be a reforming liberal while trying to make everyone happy. I learned the hard way that this made no-one happy instead. My signature reform, updating Sordland’s authoritarian-era constitution, failed to pass. Saying yes to everyone’s policy wishlist led the country into a debt crisis. The economy cratered. Next to that, my achievements (increasing access to healthcare and education, strengthening opportunities for women, befriending a Great Power, and deterring a would-be invader) paled: I lost re-election by a landslide. The conservatives hated my economic reforms; the liberals liked me but not enough to vote for me over their own candidate; and the far left, far right, and minorities hated me, period. Looking at the list of possible endings, I was probably lucky not to be overthrown or assassinated.

I did much better in Rizia. This time, I played more cautiously, focused on establishing strong economic foundations, and gradually and incrementally advanced my reforms. I turned the country into an energy-exporting powerhouse, then used trade and energy deals as carrots to peacefully reconcile with Rizia’s estranged neighbours. At home, I reformed Rizia into a constitutional monarchy with power held by an elected prime minister; and saw Romus’s heir, Crown Princess Vina, grow into a wise, confident, and compassionate woman. Compared to the shambles I made of Sordland, this was night and day. But perfection eluded me; I failed to recover lost Rizian land from the neighbouring dictator.

Less predictable than a strategy game — but also scripted and finite

While Suzerain is not a strategy game, it does share similar themes. In some ways, I find Suzerain more convincing:

- Strategy games are mechanically-driven, so they require transparent rules and predictable outcomes.

- Suzerain can be more opaque, and throw more unexpected events at the player, because it is narratively-driven. Nasty events are part and parcel of the story.

The flip side is that strategy games are unscripted and replayable: new events unfold each time. Suzerain has a wealth of content, but it is scripted and finite. Yes, there is a lot I haven’t seen. Yes, there are many paths I could take on a replay — I could follow different ideologies1, befriend different characters, or execute better on my original goal. But I still know what happens next. As someone who incessantly replays strategy games but plays narrative games once, so far I’ve yet to replay either story in Suzerain.

Conclusions

For anyone interested in their subject, and who enjoys this kind of narrative game, Suzerain and “Kingdom of Rizia” are easy recommendations. There is something authentic in how the base game and “Rizia” bring their messy, complicated countries to life — and while I’ve focused on the turmoil, my experience in “Rizia” showed how the game depicts hope as well. I’d love to see more content in this universe.

- But not become a murderous authoritarian. Some of the content I’ve seen is pretty disturbing. ↩

Old World: a pathbreaking historical 4X game

Old World is a 4X strategy game set during classical antiquity that I have played on and off since it launched on Steam, back in May 2022. It is, hands down, the most unique and innovative historical 4X game I’ve played (the other recent ones being Humankind and the Civilization series):

- First, for how it blends 4X game mechanics with other genres.

- And second, for its own, novel ideas.

These ideas successfully come together to make Old World one of the best 4Xs in any genre.

Enjoying this site? Subscribe to updates here:

Blend of 4X strategy + narrative elements

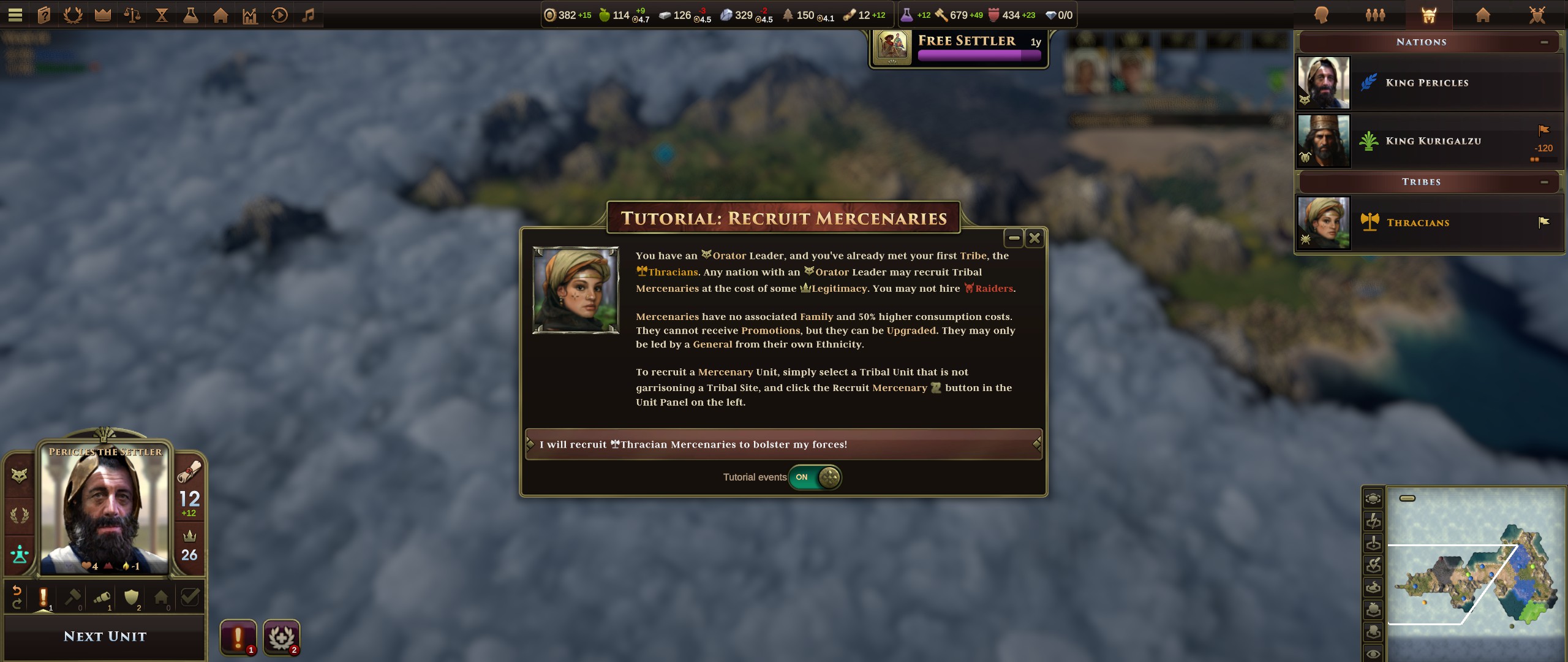

In many ways, Old World feels like a cross between a classic 4X game, narrative games like King of Dragon Pass,and, to some extent, grand strategy games:

- The basic mechanics are those of a turn-based 4X: explore the map, settle and develop cities, research new technologies, train units and march them to war, and build Wonders of the World, all in pursuit of defined victory conditions.

- Other mechanics are closer to a GSG or a narrative game:

- Rulers and officials are named characters with traits, lifespans, opinions, and relationships to one another.

- Narrative events frequently pop up: characters scheme, fall in love or quarrel; emissaries show up to present trade deals, marriage proposals, or demands; children take after or rebel against their parents; sages appear in court to offer their services; noble houses clamour for favour; exiles and escaped captives ask for sanctuary; and many more.

These “layers” of mechanics tie back to one other. For instance, character traits matter beyond simple “+1” bonuses. Rulers have different abilities depending on their character class: Diplomats can form alliances, Orators can hire tribal mercenaries, Scholars can re-roll available technologies, and more.

Novel 4X mechanics

On top of these building blocks, Old World adds its own unique ideas. For example:

- The ambitions system, which lets players choose and shape victory conditions on the fly.

- While Old World offers traditional victory conditions such as points, the main way for human players to win the game is by completing 10 ambitions — goals that the player chooses for each ruler.

- Ambitions last the life of the current leader plus a short grace period, and each leader will typically only live long enough to achieve a handful. As such, this makes it important to choose ambitions that are achievable and that align with the intended play style. I prefer playing 4X games as a peaceful builder, so I aim for ambitions like “build three universities” and “control six cities with Legendary culture”.

- The orders system: the player can take a finite number of actions each turn, limited by the number of “orders” available (as the game progresses, better-developed empires with appropriate laws will have more orders).

- This naturally creates “interesting decisions”, as what happens every turn will reflect the player’s priorities.

- It also means that certain decisions have opportunity costs — in particular, fighting a war will absorb a lot of orders that could have been used to move workers around and develop buildings.

- The role of chance: in several places, the game randomly determines the available options.

- For instance, there are different choices for educating the royal heir, each of which unlocks several potential classes. When she or he grows up, I can choose between two of the available classes — but not which two. So, I can increase the odds of getting a Diplomat or Orator in the next generation by choosing a political education, but I can’t guarantee it.

- Other examples include the game randomly determining which techs are available to research out of those unlocked; or which Wonders will be available in any given game.

Successfully bringing it together

The result is a fluid, dynamic game where the situation and the appropriate strategy evolve over time1. Events can open up unexpected opportunities: in my last game, when my ruler died in the midst of a long-running war against the Gauls, the Gauls sent a delegation to my new ruler offering to bury the hatchet. I took them up on it — and with my new, Diplomat ruler, I eventually negotiated an alliance that let me peacefully settle on Gaulish lands.

The ambitions system helps keep the late game interesting. Once, I came from far behind and still won by focusing on achievable ambitions (and staying away from any that required me to go to war — something that wouldn’t have been feasible against larger, more powerful empires). Instead, I triumphed as a builder and lawmaker via ambitions such as “build four Wonders, one of them Legendary” and “make all noble families friendly while enacting all laws”.

The combination of events, characters, and gameplay also leads to memorable emergent narratives:

- In my first game, my ageing ruler and his wife had a miracle child late in life after praying to the gods.

- In my last game, a brother returning from distant lands brought a Gaulish wife and drama in his wake as I played out different saved games: once he went insane after his wife’s death, and another time he murdered his nephew.

- In my current game, an ambitious “rising star” courtier demanded a royal marriage (I said yes) and another one demanded that I abdicate and hand over the throne (I said no … emphatically)2.

- Romulus & Remus hate each other, so if playing Romulus, it can make sense to follow the myth and take out Remus first3.

- And more — I’ve just scratched the surface.

Incidentally, while I’ve focused on the unique aspects of Old World’s design, it also gets the basics right. My favourite example here is that while military AI is a frequent bugbear in strategy games, Old World’s computer players are ruthless and effective at waging war. They muster large armies in safe territory and then commit them en masse, hunt down weakened units, and aren’t fazed by the “one unit per tile” (1UPT) rule.

The trade-off is that being unique comes with a learning curve. Old World has a detailed PDF manual, a good tutorial, and plenty of tooltips that explain what I can do. Knowing when to do something is trickier. Even as an experienced player, every time I come back after a break, I find myself Googling strategy questions or browsing Discord to refamiliarise myself.

Conclusions

Old World is the historical 4X game that I wish more genre fans — and especially, more strategy and 4X developers — would play. It is rich in new ideas, from specific mechanics such as orders & ambitions to the overarching concept of enriching a 4X game with characters and events. And it uses these ideas to keep the late game feeling fresh.

Other developers could learn a lot from Old World’s approach, and if you’re interested in similar games, check it out — I promise you it will be original.

Further reading

Design Director Soren Johnson’s blog, “Designer Notes”, has a wealth of content about Old World’s design, including this post on victory conditions.

Note: I received press copies of two DLC — “Wonders and Dynasties” and “The Sacred and The Profane” from Hooded Horse, the game’s publisher. I bought the base game and the other DLC myself.

- Contrast the modern Civ games, which require picking a victory type and strategy before even starting. ↩

- The latest DLC, “Behind the Throne”, added this mechanic. Rising stars have excellent stats but also tend to have designs on the throne. Giving them the opportunity to shine can be a calculated risk. ↩

- Most of Old World’s starting leaders are historical figures; the mythical Romulus of Rome and Dido of Carthage are exceptions ↩