Note: Storytelling in Dominions 3, part of this feature series, is available off-site. You can read it at Flash of Steel.

(Note: this article contains moderate spoilers for the game.)

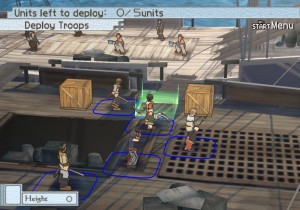

Elaborate backstories are part and parcel of speculative fiction. Fantasy’s defining work, Lord of the Rings, is above all a work of worldbuilding, while science fiction authors have long created detailed “future histories” to tie their works together. Given the extent to which RPGs grew out of this literary genre, it’s no surprise that RPG designers followed suit – a trend at its most visible in the lore codices of recent titles such as Mass Effect and Dragon Age. But in my opinion, few games have done it as well as a little-known 2006 Playstation 2 JRPG, Valkyrie Profile 2: Silmeria (developed by tri-Ace and published by Square Enix).

Very, very, very loosely inspired by Norse mythology, VP2 followed the adventures of Alicia, an exiled princess sharing a body with the valkyrie Silmeria*. The game offered a lengthy plot featuring wrathful gods, magic MacGuffins, swordsmen and sorcerers – but if the plot were all VP2 had, I would not be writing this post. It simply wasn’t that great for the first two-thirds of the game, though it did pick up sharply towards the end. Rather more satisfying was VP2’s character growth: Alicia went from a frightened girl dependent on Silmeria (this wallpaper says it all) to a mature, confident heroine, complete with new voice clips in battle. But while this was rewarding, it was still anything but groundbreaking – after all, character growth is the bread and butter of fiction.

Where VP2 uniquely shone was the way it brought its world, past and present, to life. Part of this was a combination of art design and music. The soundtrack was serene as you traversed the sunlit idyll of the Kythena Plains; ponderous in a dark, haunted forest and lilting in a magical one; chirpy in the metropolis of Villnore and ethereal as you crossed Bifrost, the breathtakingly spectacular bridge to the heavens. Even ruins, the stock setting of fantasy RPGs, were distinct: when Alicia journeyed through a half-submerged temple, the pensive music echoed the lost splendour around her – very different from the conventionally heroic theme that accompanied a trip through an ancient volcano.

And the wonders of VP2’s world were more than skin deep. While your party included plenty of storyline characters, you could also recruit up to 20 einherjar – the spirits of long-dead warriors, chosen by Silmeria to fight for the gods – randomly chosen from a pool of 40. The storyline characters (who appeared in the game’s plentiful cut-scenes) were far more fleshed-out than any one einherjar (who had only a few lines of dialogue apiece**). But as a group, I think the einherjar received by far the better deal. That was because each character, storyline or einherjar, had backstory in the form of a character profile accessed from the party screen – and the einherjar backstories, spread over a thousand years of in-game history, were extensively woven together. They interwove with the towns you visited in-game (your party might include a given location’s mythical founders), but more importantly, they interwove with each other. If you read the profiles of two or three einherjar, you might find that they’d journeyed together in their youth; split up to take opposite sides in a war; and met their separate ends after that. A kingdom home to four or five einherjar in one generation might disappear a hundred years later, brought down by an einherjar from a rival land; that conqueror in turn might die ignominiously to a poisoned arrow.

This would have been impressive enough on its own. But there was also a second, deeper layer: the profiles weren’t always true. For instance, this is what the game had to say about Woltar the sorcerer, who joined in one of the earliest dungeons:

A ruthless alchemist who kidnapped the Queen of Crell Monferaigne in 746 C.C. Hiding out in the hinterland of Salerno, Woltar was rumoured to have spent his days and nights engrossed in horrifying experiments. However, in 752 C.C. he was found and punished by officers from Crell Monferaigne. A month after the queen was rescued from her prison, she took her own life by throwing herself from atop the castle wall.

The mental images are horrific – but false. Here’s what really happened: Woltar and the queen eloped. They lived happily and even had a daughter together, before the king’s men found Woltar, killed him, and brought the queen back, only for her to kill herself out of grief for her lover. Their daughter’s ending was no happier, as you found out if you recruited her: she was murdered years later on the orders of her stepbrother, the prince.

The tragic tale of Woltar and family was just the tip of the iceberg. The einherjar backstories were packed with sorrow: the woman who, believing false accusations, arranged for her sister’s death – and who killed herself upon discovering the truth; friends who met on the battlefield after supporting rival kings; the loyal sorcerer whose suspicious liege abandoned him to torture and death. And while the game played fast and loose with its Norse inspiration, this was one area where it felt absolutely true to my knowledge of myths from round the world – look at how few of the ancient Greek heroes made it to a happy ending.

But the einherjar backstories weren’t just about sorrow, containing as they did other emotions that we should feel in the presence of epics. These were warriors brave enough to be chosen as the champions of the gods, and thus, heroism – and triumph even in death – were prominent: the friends whose sacrifice saved their home from conquest; the trio who sealed off the gateway to the netherworld, something which could probably have made a story in its own right. There was even poetic justice: the sorcerer responsible for the deaths of four other einherjar never got to enjoy his triumph, courtesy of an arrow through the heart. His assassin? None other than another einherjar.

Unfortunately, despite all the above, rock-solid gameplay*** and praise from the critics, VP2 never achieved even the cult-classic status of its predecessor. Sales (according to VGchartz’ estimates) were measly, and even within the JRPG genre, it seems to have ended up little more than an obscure footnote. But it left its impression on me. Long after details of gameplay and plot faded from my mind, I remember the game’s locations, beautiful, diverse, and filled with character. I remember the game’s spiderweb of einherjar relationships, complex and deep enough to do any novelist proud. I remember how enthralled I was to see the pitiless history of VP2’s world played out through the lives and deaths of the einherjar; and I remember the emotions their stories provoked. True, this is not a method that could be used by many games, given how the valkyrie/einherjar conceit tied in with the game’s lore – but VP2 made the most of it. To this day, I’m glad to have experienced VP2’s storytelling, and it remains one of my favourite games.

* An invention of the game, not an actual mythological figure.

** Unlike the first game, where every character you recruited was an einherjar, each of whom received an introductory cut-scene of his/her own.

*** To be fair, sometimes it was a bit too rock-solid – the game was rather hard.

Resources

Eurogamer review

Order Valkyrie Profile 2: Silmeria from Amazon (US)

I hope you enjoyed this post! To quickly find this post, and my other feature articles, click the “features” tab at the top of this page.

Like this:

Like Loading...

I’m nine episodes into Persona 4: The Animation, the anime adaptation of the excellent PS2/Vita RPG; as I would like to eventually finish the game (I am “only” 30 hours in), I have paused at this point in the anime to avoid spoiling myself. The anime is a lot of fun, worth the money I spent on it… and yet, I can’t shake the feeling that it is a guilty pleasure.

I’m nine episodes into Persona 4: The Animation, the anime adaptation of the excellent PS2/Vita RPG; as I would like to eventually finish the game (I am “only” 30 hours in), I have paused at this point in the anime to avoid spoiling myself. The anime is a lot of fun, worth the money I spent on it… and yet, I can’t shake the feeling that it is a guilty pleasure.