I’m slowly playing Metaphor: Refantazio, my other contender for 2024’s game of the year (alongside WARNO and perhaps Indiana Jones & the Great Circle).

Released in October 2024, this is an RPG that brings Atlus’s beloved Persona formula to a new, secondary-world fantasy setting. Along the way, it incorporates Persona’s strengths: turn-based combat, characters and voice acting. So far, I love it.

What do you do in the game?

As with the Persona games, there are two main layers in Metaphor:

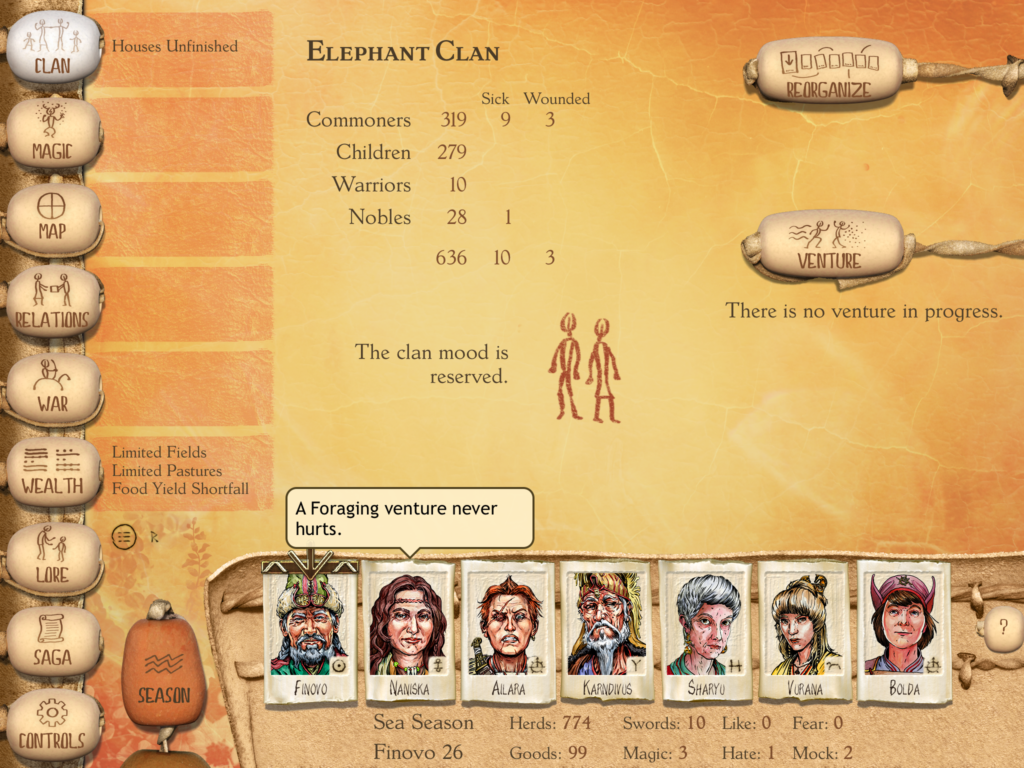

- Time management / social simulator — The game’s plot progresses according to a schedule and eventually it moves on, ready or not. To prepare, the player has 2 time slots per in-game day. These can be used to spend time with party members and other friends, level up social skills, travel, or battle through dungeons (which takes up the entire day).

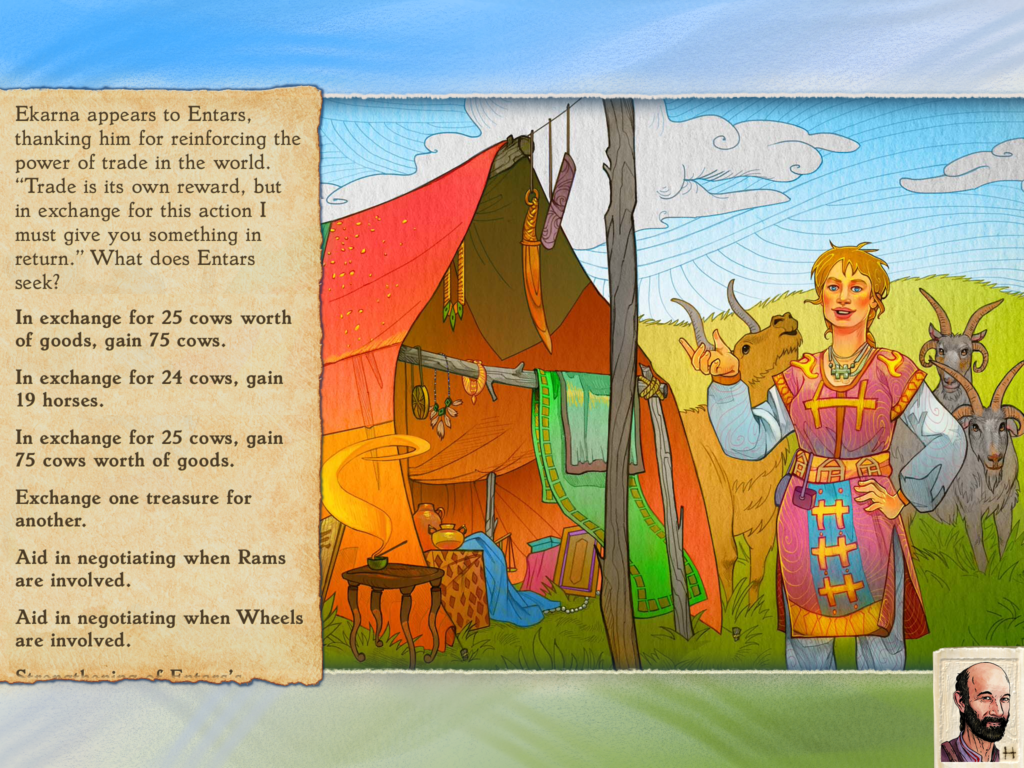

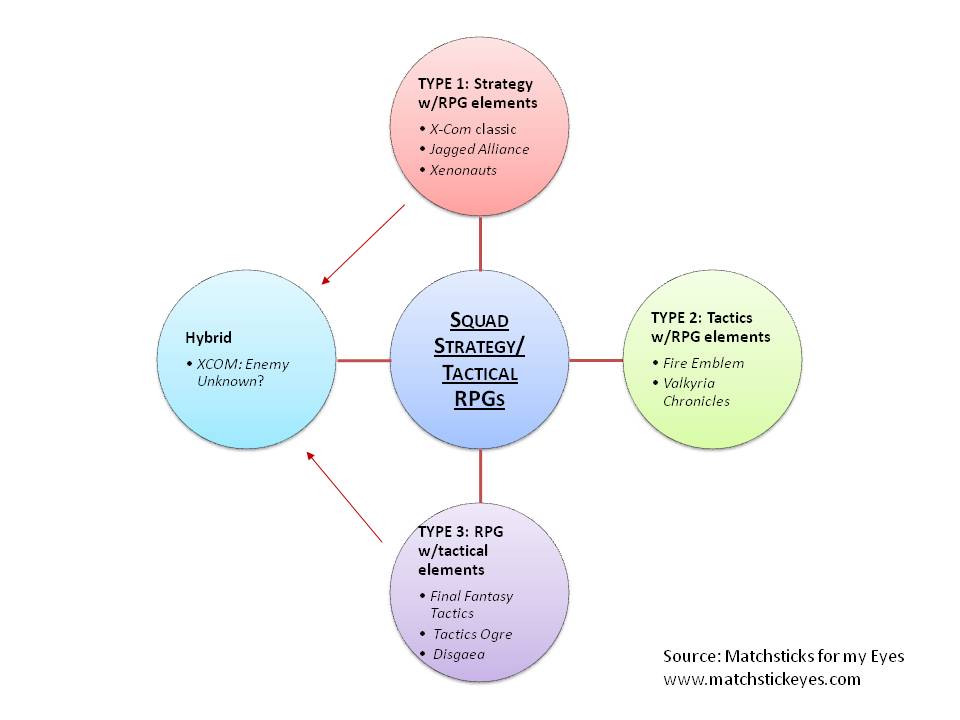

- Dungeon-crawling party RPG with turn-based combat — The basics will be familiar to Persona players. As in the Persona games, different monsters are vulnerable to different types of damage, and striking a monster’s weakness grants an extra turn.

- What is new is that it works on a class-based system, instead of the party members having fixed Personas. Different classes have different skills and can inflict different types of damage (for example, mages can cast fire, ice, and lightning spells; knights can draw enemy fire; brawlers inflict heavy strike damage at the cost of their own health; and so on).

- Characters can switch classes at will, inherit skills from other classes, and gain access to team skills that depend on the classes present in battle. As such, part of the appeal is planning out builds, cross-training characters, and fielding teams whose members complement each other and cover the relevant bases for that dungeon.

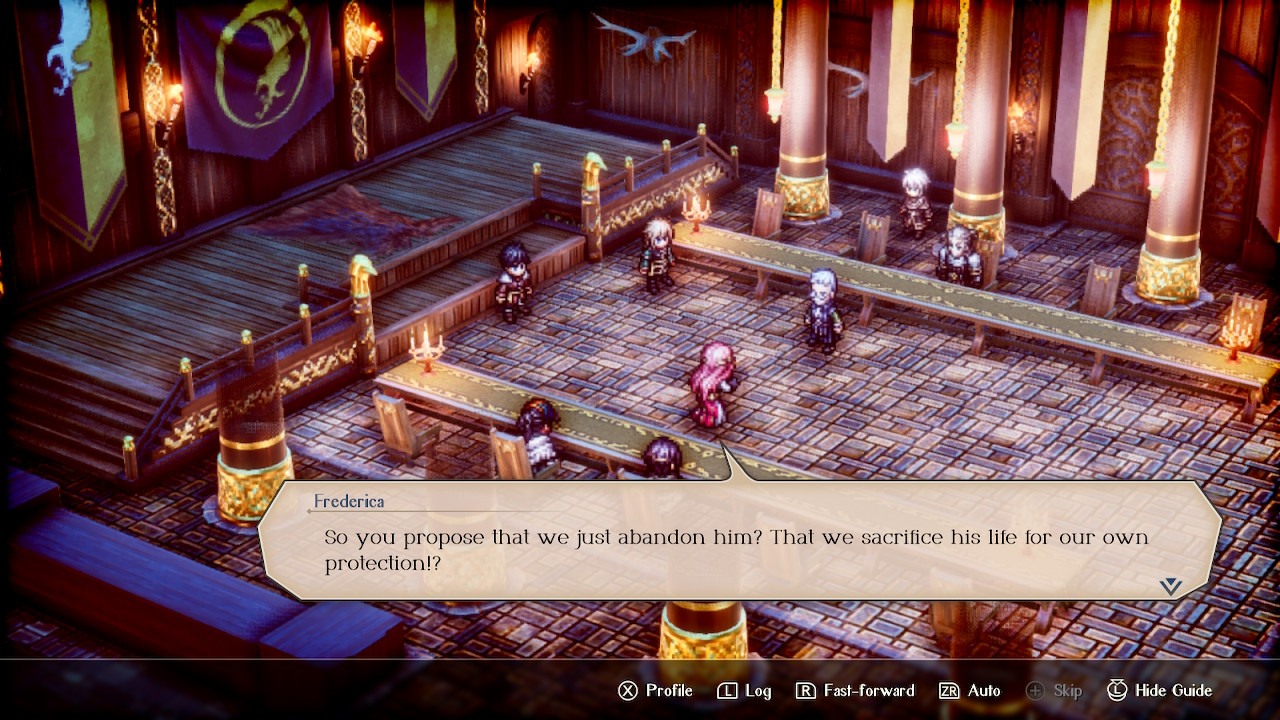

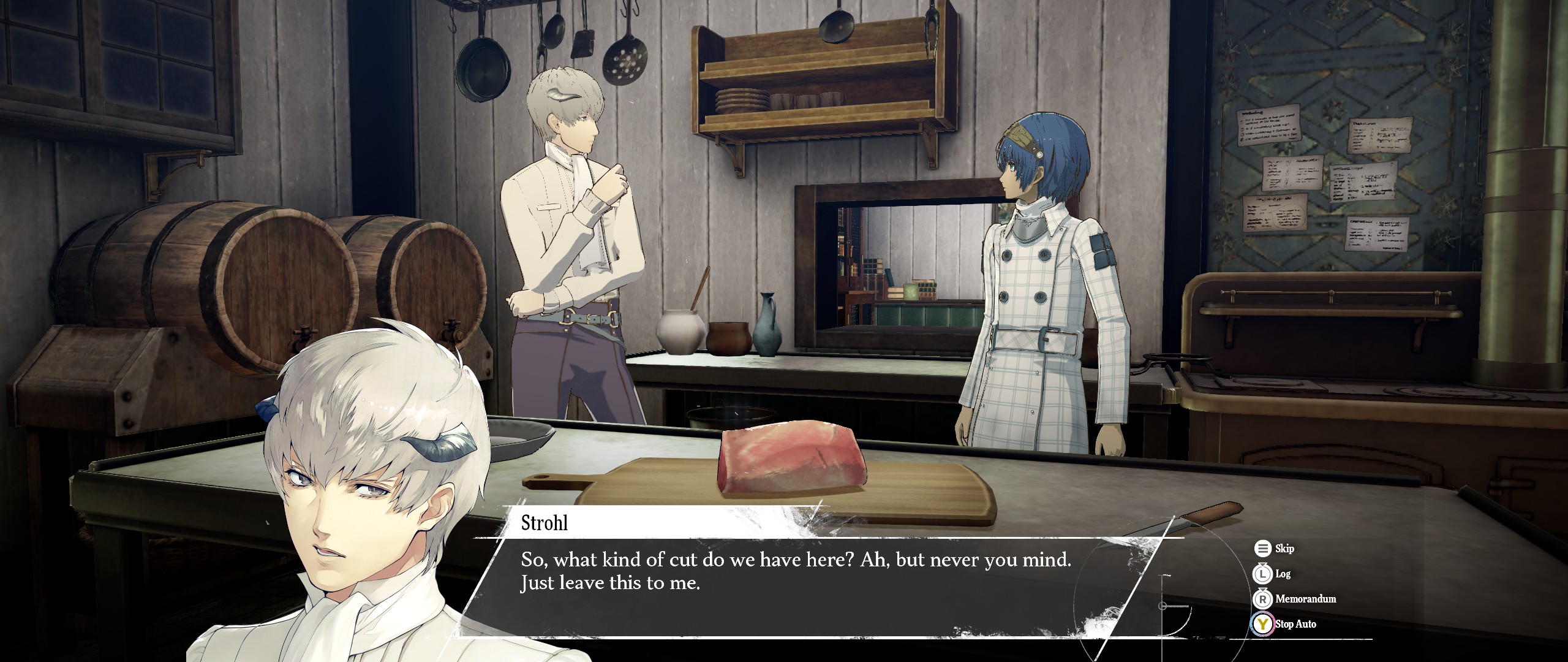

While not a third layer per se, playing Metaphor also involves a lot of time watching the narrative unfold — this is a very talky game, especially early on, and the time management doesn’t kick in until after the introduction. Fortunately, the writing is generally good — on which more below.

The time management aspect does require some willingness to deal with FOMO. Recently, I came back to the game after a period of dudgeon when I missed one activity (and the associated achievement), debating an NPC. I debated whether to either:

- Continue; or

- Reload, rejig my schedule to fit in the debate, and re-clear one dungeon for a side quest.

Let’s just say that dungeon went much more smoothly the second time…

What do I like about the narrative?

The best part of the Persona games, the characters and the voice acting, is still present.

At its core, this is a story about a group of friends. Each party member — so far I’ve recruited three, besides the main character — feels distinct, in terms of their dynamic, storyline, and personal demons. And there is something very wholesome about the way they and the main character support each other through thick and thin.

More broadly, Metaphor has one of the most unique fantasy settings I have ever seen. This does not feel like a “typical” fantasy world, from its surface-level elements (such as the aesthetic) to its deeper ideas. Great fantasy and science fiction use their worlds to say something about ours — and that’s exactly what Metaphor does.

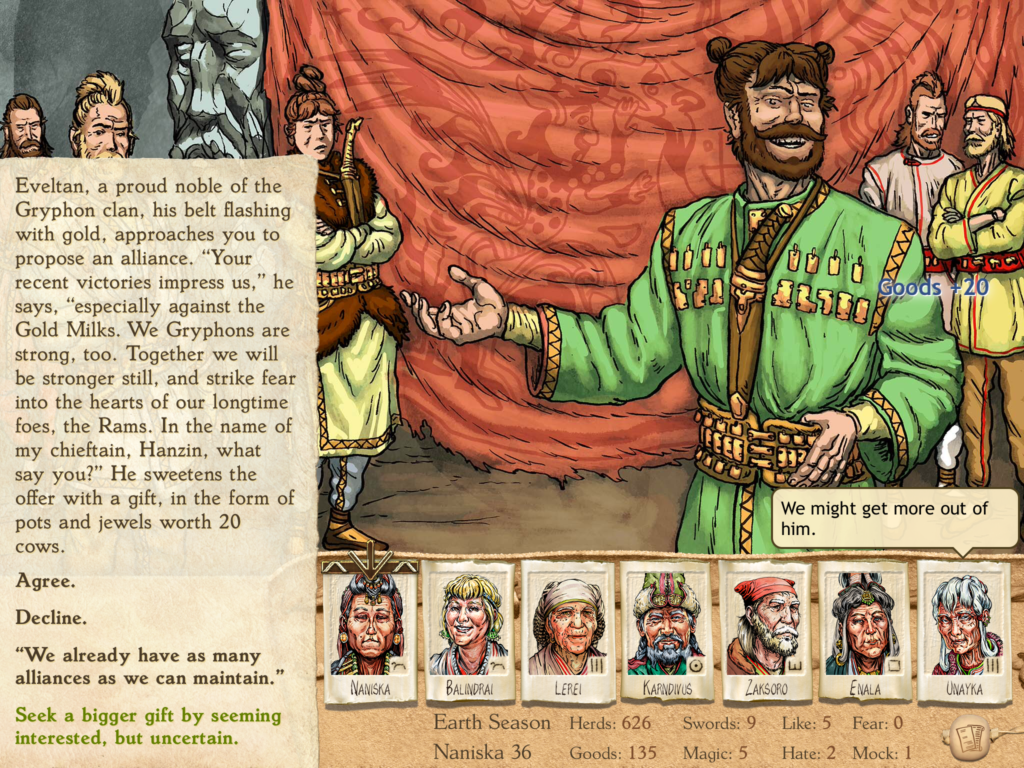

Metaphor’s setup is that of a dystopic fairy tale. The king is dead, monsters stalk the land, and the dominant races — led by the horned clemar and the sharp-eared roussainte — shove the “lesser” races — such as the Yoda-like eugief and the fox-like paripus — into the dirt.

But for the heroes, things don’t have to be that way. They draw inspiration from a fantasy novel depicting a Utopia where glass buildings soar into the sky, where people choose their leaders, and where there is only one species that lives without hatred — in other words, a very, very idealised vision of our world. This is a really interesting message (and somewhat “meta” commentary) about how we, in the real world, use idealised fantasy settings for escapism. Why wouldn’t the same apply in reverse?

My biggest complaint is the heavy-handedness of the narrative. So far:

- The villains are cartoonishly evil;

- The world’s problems, such as prejudice between the fantasy races, are exaggerated to the point of melodrama. In other words, this is neither a nuanced nor a sophisticated examination of these issues.

As a final note, the game has hinted that the world is something other than what it seems. I have my own theory and I wonder if I will be proven right.

Conclusions

In every way, so far Metaphor has been a worthy heir to the Persona games.

- Mechanically, it’s just as satisfying beating up monsters as it was in Persona, now with the added layer of class and party customisation.

- Narratively, I like these characters, I like spending time with them, and I care what happens to them.

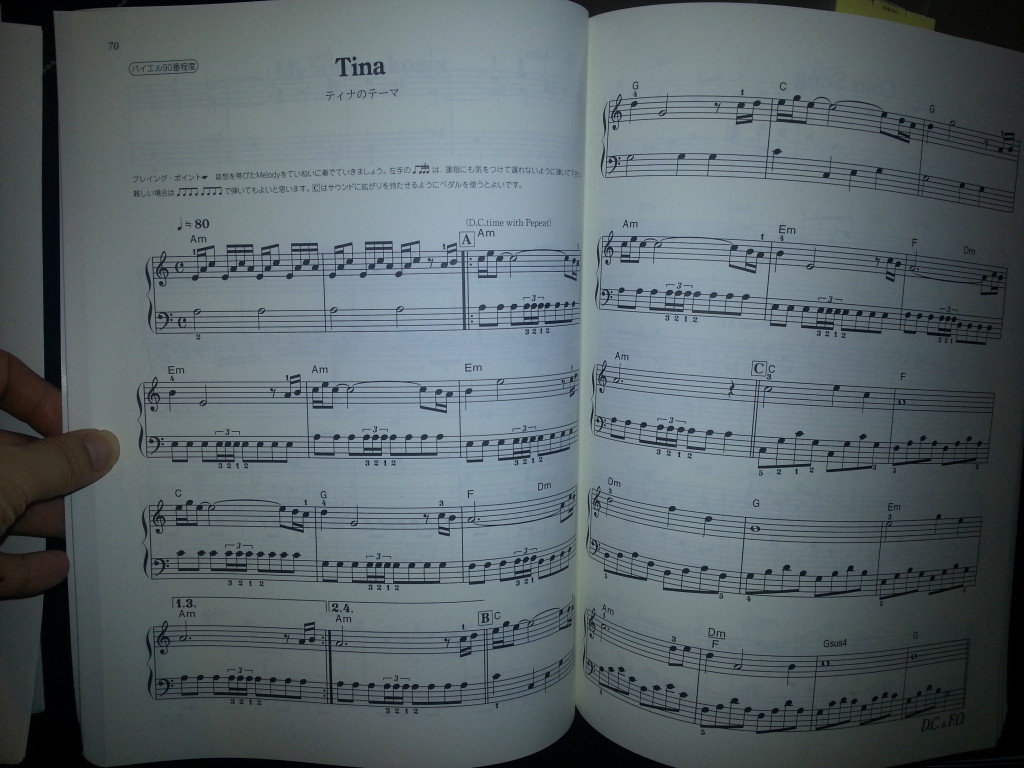

- Aesthetically, the art is striking and vivid, and there are some excellent pieces in the soundtrack — perhaps a subject for future Musical Mondays?

For Persona fans, or anyone interested in the premise, this is an easy recommendation. If you’d like to try it first, check out the demo — it contains hours of gameplay and is what convinced me to buy.