Set during the sixteenth-century zenith of the samurai, Creative Assembly’s Total War: Shogun 2 (2011) was one of the best strategy game in years. CA soon followed it up with a first expansion, Rise of the Samurai¸ which wound the clock back to the Gempei War of the twelfth century. Now the latest, stand-alone expansion, Fall of the Samurai, wraps up almost a millennium of Japanese civil strife by moving forward to the nineteenth-century Boshin War. How does it compare to its illustrious parent?

The promise

Fall’s greatest strength is the clarity of its theme: this is a game about change, in a way that no other Total War game has been. In fifty years, Japan went from a land of shogun and samurai to a power that could beat a Western empire; and from look to feel to mechanics, that wrenching transformation is written all over Fall.

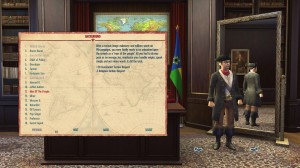

You’ll notice the game’s new aesthetic straight away: riflemen face samurai in the game’s loading screens, the new map looks like a nineteenth-century atlas rather than a Japanese scroll, most of the playable daimyo are dressed in Western uniforms. As you build up your empire, you’ll see more wonderful touches in the graphics and flavour text. Trains puff smoke and chug through little tunnels. Generals receive stat boosts by picking up Western knick-knacks: pianos, penny-dreadfuls and more. New technologies are accompanied by poetic blurbs, running the gamut from bleak to resigned to hopeful. (Compare the descriptions for six techs: “arms deals”, “modern army”, “cordial relations”, “gold standard”, “capitalist production”, and “charter oath”.)

But text is only part of the story. Gameplay mechanics are another vital way to communicate theme, and this is where Fall shines. As you fight your way across Japan, you’ll witness the end of an era, or more precisely, the transition through several eras, compressed into a single frantic period. Within the span of a single campaign, you’ll go from the shock-dominated battlefield of the Middle Ages, through the pike-and-shot era, to the fire-dominated age of industrial war. At the start of the game, samurai and even levy spearmen will roll right over peasant musketeers, but soon enough, trained soldiers with modern rifles will take their toll on anyone who approaches on foot. As firearms get better and better, riflemen more and more skilful, and artillery more abundant, modern armies will eventually massacre hordes of samurai or peasants with barely a scratch.

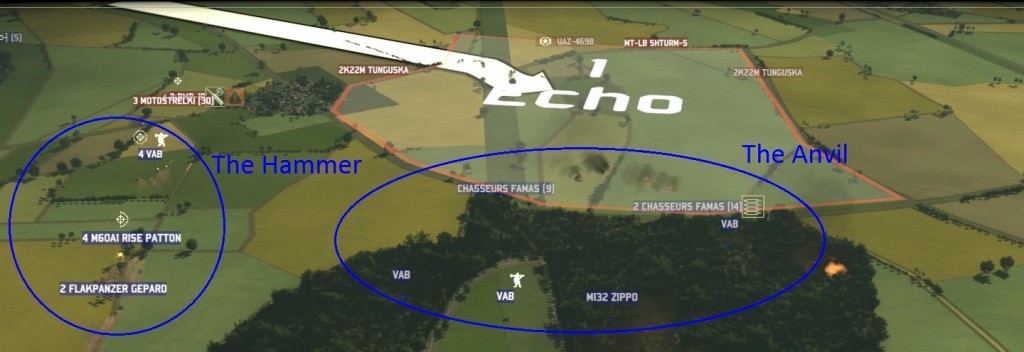

As such, modern weaponry is a literal game-changer. But not just due to its lethality. Riflemen do what bowmen have always done in the Total War games, just much, much better. Even greater transformations are visible in the other arms, cavalry and artillery, and what they do to the overall feel of combat. Traditionally, battles in the Total War series were about pinning the enemy’s infantry in melee with your own, preferably heavier infantry, then swinging around with cavalry to roll up the enemy from behind. Heavy infantry beat spearmen, spearmen beat cavalry, and cavalry beat anything if it attacked from behind. Even in the gunpowder-era games (Empire and Napoleon: Total War), battles were decided after the armies were close enough to see the whites of each other’s eyes. Not so in Fall. Spearmen still counter cavalry if they catch them in hand-to-hand… but now the cavalry have guns aplenty, and they need them. The best counter to a charging lancer is no longer a man with a pike; it’s another horseman with a gun, or perhaps even a well-trained rifleman. And woe betide the spearman who tries chasing a revolver-armed horseman. That is, if that spearman survives artillery that long. The inaccurate cannon of Empire and Napoleon are gone: American Civil War-era Parrott guns unlock early on, and they will rack up hundreds of kills per battle. Massed Parrotts will knock out even elite regiments long before they enter the fray, and later artillery is even more lethal. You will see the death of chivalry in this game, and you will see the road towards the slaughter of the Great War.

The failings

At their best, Fall’s battles might just be the finest in the entire series. The key phrase is “at their best”. All too often, the battles are not at their best, due to problems with the campaign AI. And that sums up Fall’s greatest weakness: it all too rarely fires on every cylinder. Here are some examples:

1. Land combat. Battles at the start of the game, when both the player and the AI rely on levies backed by a handful of samurai and modern riflemen, are tense and fun. The problems come later: the computer just doesn’t understand how badly quality eventually beats quantity. Even in the endgame, I’ve only seen the AI use high-end modern infantry once. I see rather more regular modern infantry (especially after installing an AI mod), but I also see lots of samurai and peasants – by this stage, target practice. All too often, the game serves up fodder instead of challenge.

2. Sea combat. The war at sea is meant to take a similar course to the war on land. Wooden ships burn en masse once explosive shells show up, and ironclads sound their final death knell. Pitched fleet battles, especially in the presence of coastal defences, can be spectacular. Unfortunately, the designers evidently thought it was fun to make the player play whack-a-mole against constant, small raiding fleets (especially on “Hard” difficulty). It’s not. The problem is exacerbated by naval zones of control that are too small; and puny coastal defences. I alleviated this with a homebrew naval mod, but I shouldn’t have to fix games myself.

3. Diplomacy. In the base game, diplomacy was “every man for himself”, but Fall divides Japan into two broad camps (based on the way religion worked in the original game): pro-Imperial and pro-Shogunate. Players of the same allegiance enjoy a healthy bonus to diplomacy; players of opposing allegiances take a serious penalty. The victory conditions reflect this: your camp has to take X number of provinces and both Edo and Kyoto, but you personally have to take far fewer provinces (14 in the short campaign, rather than the base game’s 25). And rather than “you vs the world”, realm divide now functions as the final Shogunate/Imperial showdown: only the opposing camp will attack you, while clans of the same allegiance will rally behind you instead.

On paper, this is a great idea. And when it works (i.e. when the war between the two factions hangs in the balance), it works well. It’s very cool to be part of, as opposed to the focus of, a greater conflict – especially after realm divide. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work: the course of the broader war is a crapshoot. If your faction does too well, the game is boringly easy. If your faction does too badly, then the game turns into a grinding slog. It’s aggravating when such a key part of the overall experience comes down to luck of the draw.

4. Difficulty and balance. More broadly, Fall’s campaign feels as though the developers didn’t have the time to properly tune the game’s balance. It shows up in the difficulty settings: on “Normal”, the campaign is often rather easy. “Hard” is a different story, but not because the computer is cleverer. No: everything costs roughly 15%-20% more, and the computer players team up for a game of kick-the-human. It shows in the victory conditions: requiring that your camp hold Edo and Kyoto might be historically accurate, but it skews the game, since both (particularly Edo) are within Shogunate territory. As a result, my Normal Shogunate campaign felt much shorter and more anticlimactic than my Imperialist campaigns. (Compare the base game, in which you fought your way towards Kyoto, in the centre of the map.) It shows in the game’s economy. The developers clearly intended money to be scarcer: trade nodes have been removed, most farmland is poorer than in the base game, and everything costs more. But they went too far: now money is artificially, annoyingly scarce unless you beeline for “fertile” and “very fertile” lands (especially bad on “Hard”). And it shows in the issues I described above. Given time, surely the developers would have fixed the AI issues, the ship spam, and so forth.

As such, my playthroughs of Fall have been a decidedly mixed bag. Playing on “Hard”, my campaigns began promisingly, with plenty of challenge and thrills, before eventually degenerating into frustration. Playing on “Normal”, one game I spent fighting small, weak clans was dead boring. One game in which the opposing faction took over most of Japan started well, but turned into a slogfest. And my final, most rewarding playthrough delivered the experience that Fall should have been from the start. I played differently that last time – by then I knew the “optimal” path to take, and I didn’t turtle (which I think helped the game’s pacing). But I also had to apply the AI and naval mods mentioned above, and I benefited from luck (e.g. with the progress of the Imperial/Shogunate war).

Conclusions

Ultimately, Fall of the Samurai didn’t live up to my hopes. Fall brings together theme and mechanics with a superb battle system, only to hamstring itself with a wildly inconsistent campaign. Its highs are higher than the base game’s – but its lows are just too frequent, and too annoying, for it to fill its predecessor’s shoes.

At the end of the day, I have to formulate my recommendation based on one wonderful campaign –and five (!) that were love-hate. And that is: wait for patches, mods, and/or a bargain sale. Buy Fall of the Samurai then. But don’t buy it now.

You can buy Shogun 2: Fall of the Samurai from Amazon (US).

We hope you enjoyed this post! To quickly find this post, and our other reviews, click the “reviews” tab at the top of this page.

Resources

Province fertility/specialty map, updated for Fall of the Samurai.

Radious’ AI mod. It’s hard to unpick the difference made by a mod, but I do think this helped the AI recruit better armies.

My homebrew naval mod. To install, simply unzip and place in the \data folder in the game’s Steam directory. Its key features are:

- Bombardment range is still 8 (or 10 for Tosa, which gets a +2 bonus).

- The Tier 1 harbour (“If this is a port, then one wall is a house!”) remains defenceless.

- The Tier 2 port now has level 1 defences (equal to the base game’s trade ports) with a range of 12. The defences are silenced at 70% health.

- The Tier 3 trade port now has level 2 defences (equal to the base game’s military ports) with a range of 12. The defences are silenced at 50% health (again, equal to the base game’s military ports).

- Tier 3 military ports and the foreign (British/French/American) tier 4 trade ports now have Level 3 defences (equal to the base game’s drydocks), with a range of 12. The defences are silenced at 30% (again, equal to drydocks).

- Drydocks, whose defences were already maxed out, have received no boost.

- The naval intercept radius is now 12.

- These changes will be reflected in the tooltips when you mouse over the buildings, but not in the in-game encyclopaedia.

The basis of my review

Time spent with the game: I estimate at least 20 or 30 hours.

What I have played: Two campaigns won (Nagaoka/Normal/Short, Tosa/Normal/Short). Four campaigns aborted: two as Nagaoka/Hard, one as Tosa/Hard, and one as Tosa/Normal. Briefly, the cooperative multiplayer campaign (Choshu/Hard, with a friend playing Tosa). A couple of multiplayer battles.

What I haven’t played: The PvP multiplayer campaign.