Better late than never!

Every year I publish a recap of that year in gaming. 2024 was a good year in terms of new releases, spread across several different genres.

Overall, including titles from previous years (mostly old favourites that I replayed) skewed my gaming heavily towards strategy.

What new releases did I play in 2024?

The new releases I played were a mix of genres — these included:

- Strategy — real-time tactics (WARNO), city-builder (Frostpunk 2), and 4X (Ara: History Untold)

- RPG (Metaphor: Refantazio) and tactical RPG (Unicorn Overlord)

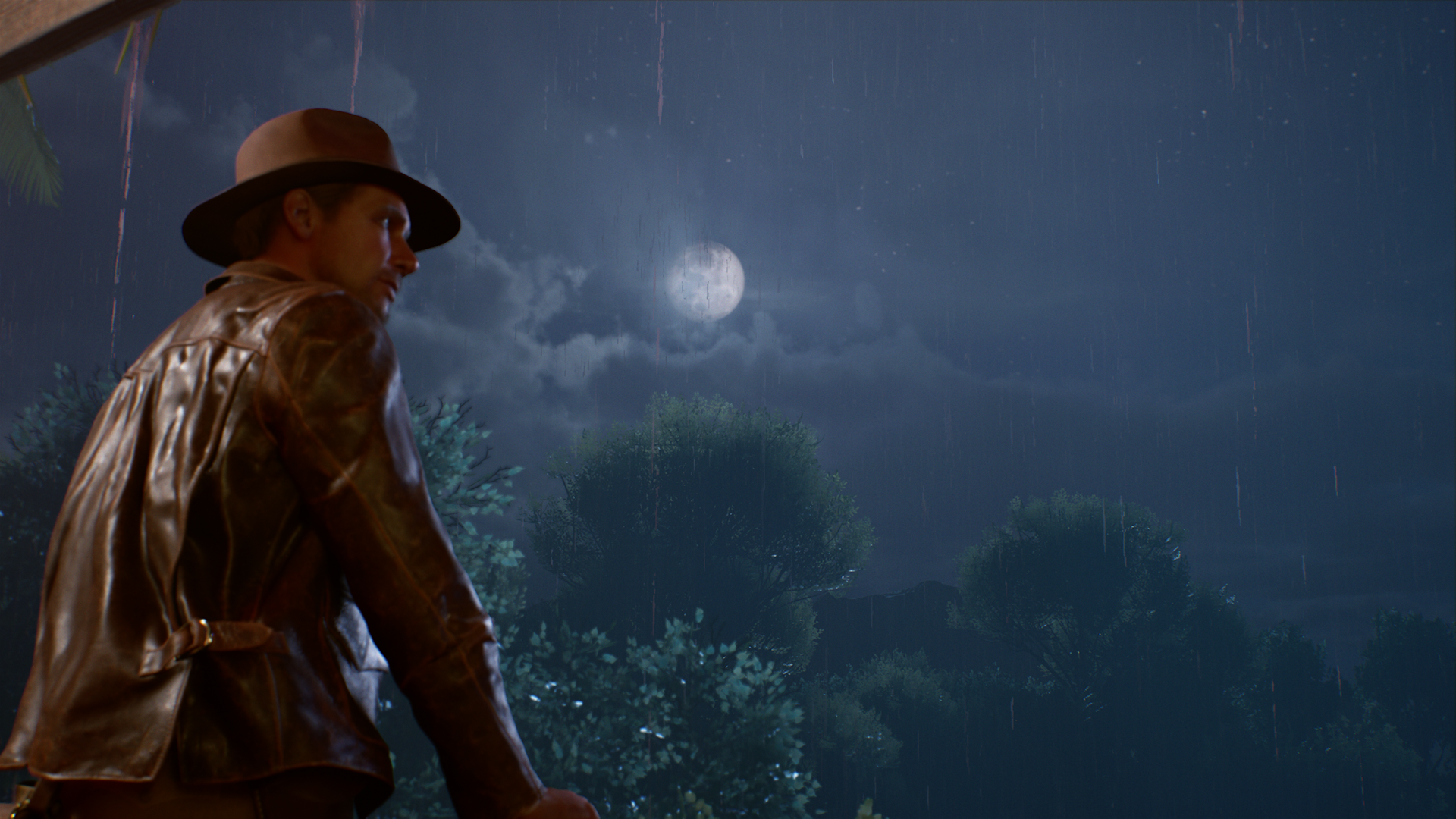

- 3D action-adventure (Indiana Jones and the Great Circle)

- 2D Zelda (The Legend of Zelda: Echoes of Wisdom)

- Simulation (MS Flight Simulator 2024)

- Interactive fiction and open-world action, if DLC counts (the “Kingdom of Rizia” expansion for Suzerain and the “Shadow of the Erdtree” expansion for Elden Ring)

Which new releases were my favourites?

My picks for Game of the Year are WARNO and Metaphor: Refantazio, both of which I wrote about.

- WARNO successfully iterated on Eugen’s real-time tactics formula, and gave me many hours of fun during an often-challenging period.

- I picked up Metaphor: Refantazio late in the year, and it wowed me with its style, dungeon-crawling, and character interactions.

The runners-up

I would place Indiana Jones and the Great Circle just a notch below. This is not so much the game’s fault as a matter of personal taste — later areas moved away from the verticality, focus on freeform exploration, and gorgeous architecture that enchanted me so much in the first area, the Vatican.

Unicorn Overlord is mechanically excellent and in terms of sheer hours, was one of the games I played most in 2024. Had the writing been better, it would be higher up my list.

What titles from previous years did I discover or revisit?

There were a lot of beefy, evergreen strategy games:

- I revisited Old World and Crusader Kings III in response to the release of new DLCs. Old World, in particular, is a perennial on my end-of-year lists.

- Anno 1800 is another perennial. I even put together a to-do list on pen and paper, as I continued working through the tremendous amount of content in the game.

- Inspired by the excellent new Shogun TV series, I revisited Total War: Shogun 2 — and finally won as the Oda clan, the first clan I ever tried!

- I revisited Terra Invicta and found it coming along well, two years after it launched into Early Access.

- I revisited Emperor of the Fading Suns (link to my original write-up from back in 2011), a classic 1990s 4X game that has been updated and re-released on GOG.

- I kept playing Rule the Waves 3, a 2023 release.

- I also tried Fantasy General 2, Field of Glory 2: Medieval, and 40K: Gladius for the first time (and dusted off FOG2‘s predecessor, Sengoku Jidai). While its production values are limited, Fantasy General 2 made a good impression on me.

Non-strategy games included:

- Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom was my favourite game of 2023, and I finished in 2024.

- I revisited Elden Ring and made it most of the way through the base game — up to the Fire Giant — as well as starting on the DLC.

- A Legionary’s Life was the standout “short-form” game I discovered in 2024.

- Revisiting Mount & Blade II: Bannerlord took much of the shine off (my original write-up from 2020), as this time the core gameplay loop felt much more repetitive. But what it does (spectacular battles), it does well.

- I discovered and enjoyed Suzerain’s base game, leading me to pick up the “Kingdom of Rizia” DLC.

- Potionomics is charming, although its central loop (brew potions, sell potions, buy ingredients to make more potions, repeat) hasn’t kept me engaged as long as some of the other games on this list.

- I continued my snail’s-pace progress through Fire Emblem: Three Houses.

- We Love Katamari Reroll was as charming as ever.

- No list of ongoing perennials would be complete without Mario Kart 8: Deluxe.

Site news

2024 was a productive year for the site!

I resurrected Musical Monday, with a mix of game, anime, movie, and even classical music.

Besides games, I also wrote about books (Megan Whalen Turner’s Queen’s Thief series), and movies (Dune: Part 2).

On a technical note, I switched to a new theme, GeneratePress.

Upcoming releases

There’s only one game release on my radar, the imminent Civilization VII.

In terms of hardware, I am very interested in the upcoming Switch 2. If Nintendo releases it at a reasonable price and with a decent launch library (a new Mario Kart is already visible in the trailer video), then I’ll look to buy it as soon as I can after launch.

I look forward to seeing you around for the rest of the year.